INDUSTRIAL JP

idstr.jp open shareDecember 13, 2017

AT-7

meiko futaba

interview

Bringing Quiet Passion and

Pride to Cutting-Edge Creation.

// meiko futaba Interview

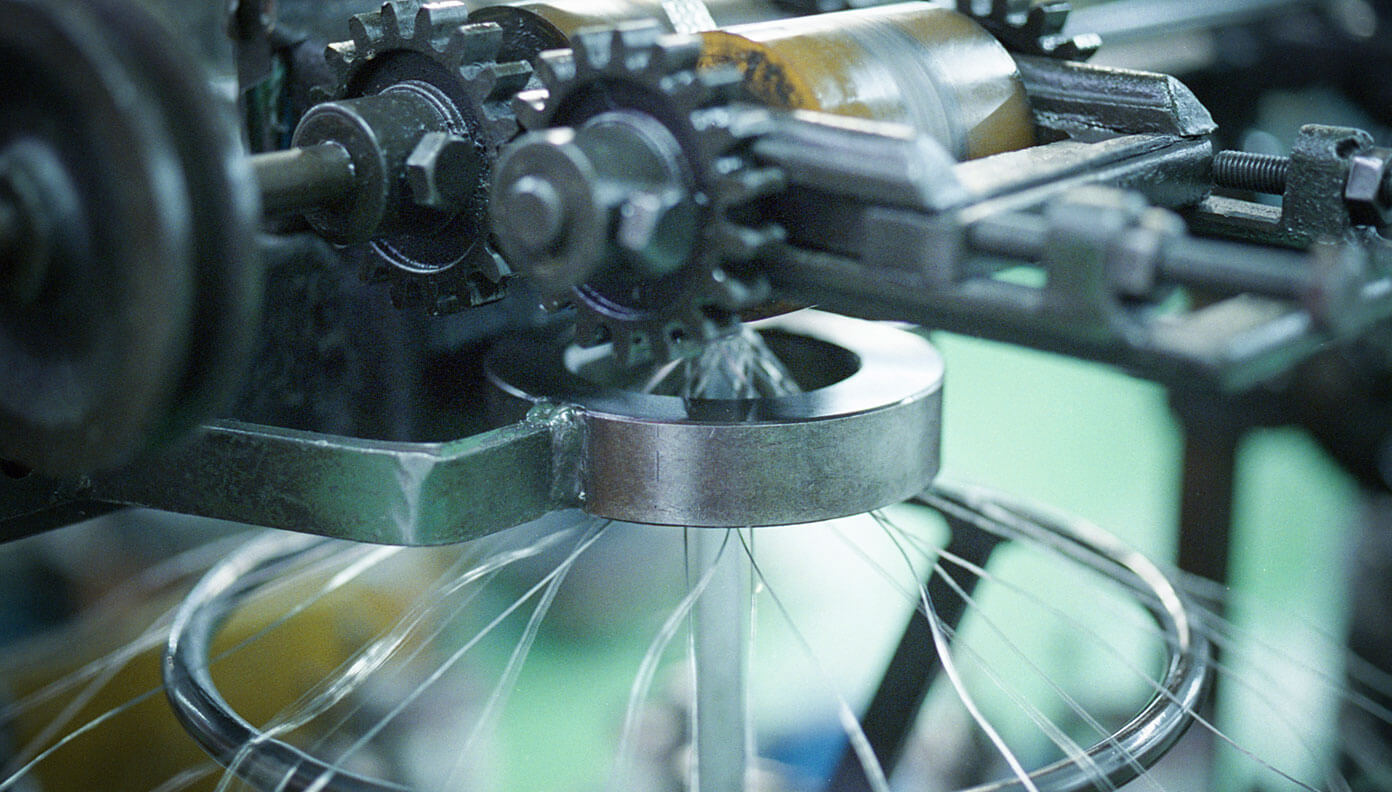

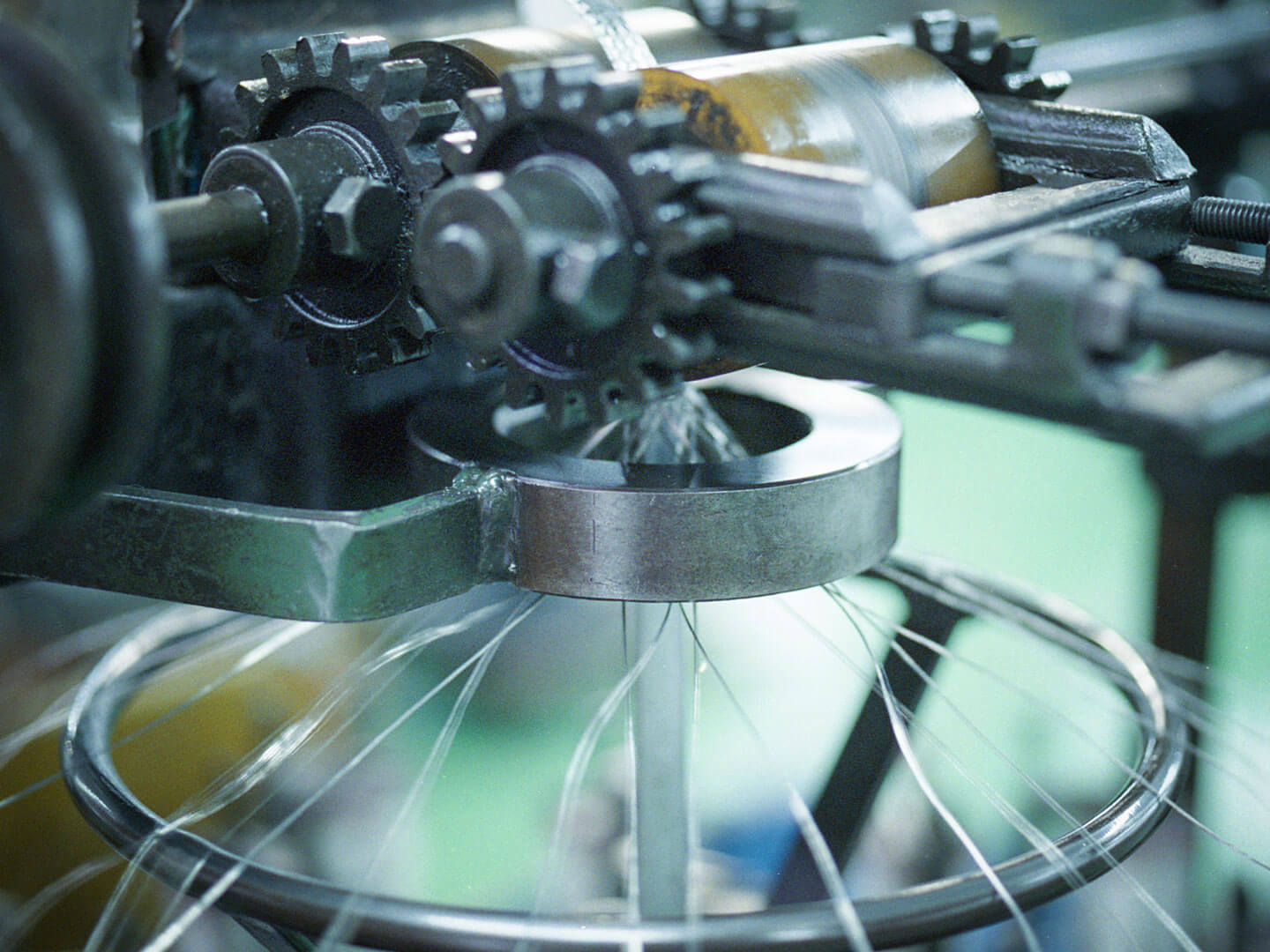

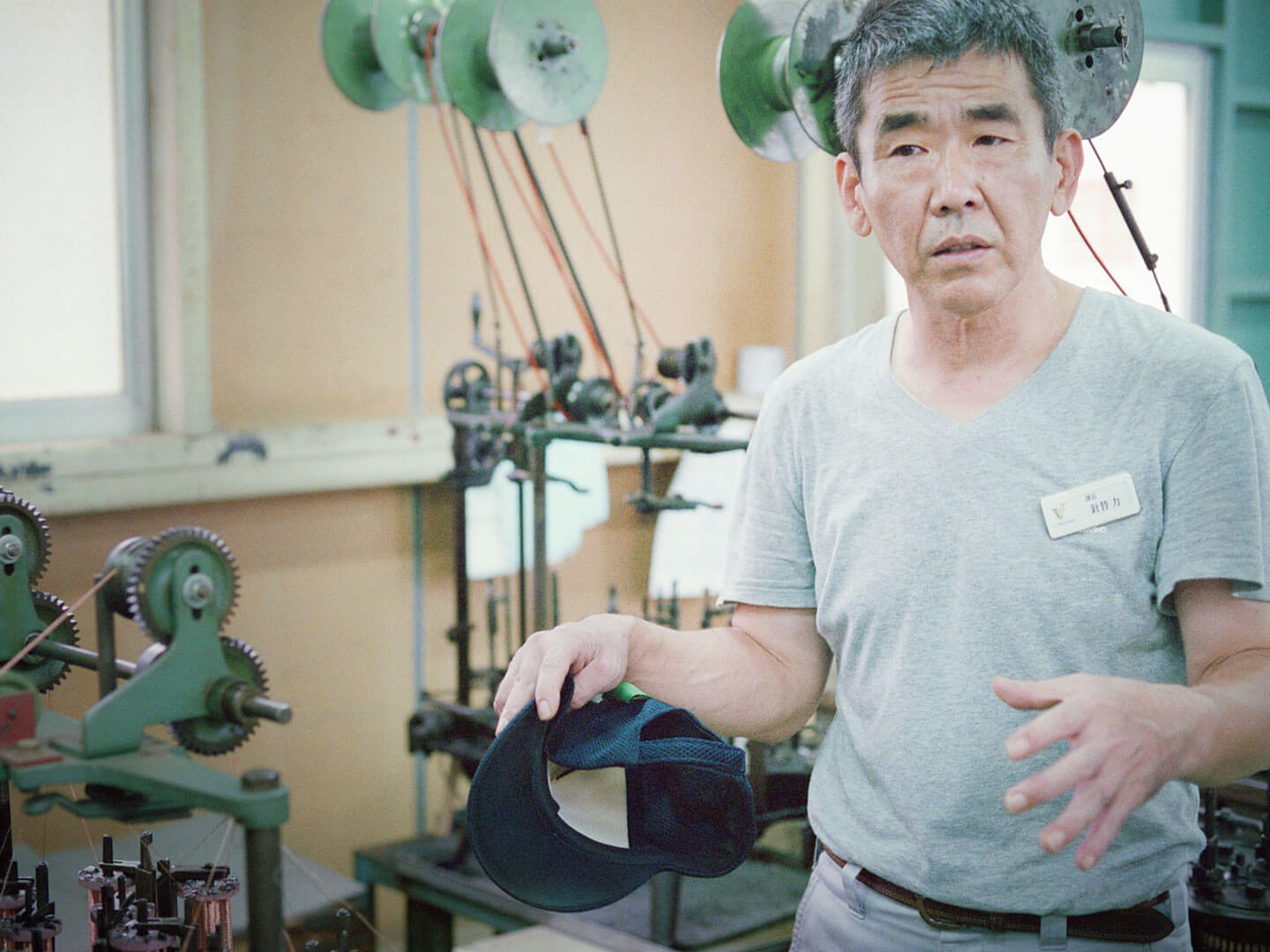

Meiko Futaba manufactures municipal electrical wires and parts for harnesses used inside of cars. They have a factory in Ibaraki, Japan. The subtle vibrations of the machinery accumulate into a constant rumble. It is here that we spoke to the factory manager and one of his veteran technicians.

meiko wire

ID-7

meiko futaba

paisley parks

Essentially, we’re weaving things from threads of metal.

I see a lot of machines spinning around a bunch of thin wires. What kind of products does Meiko Futaba manufacture?

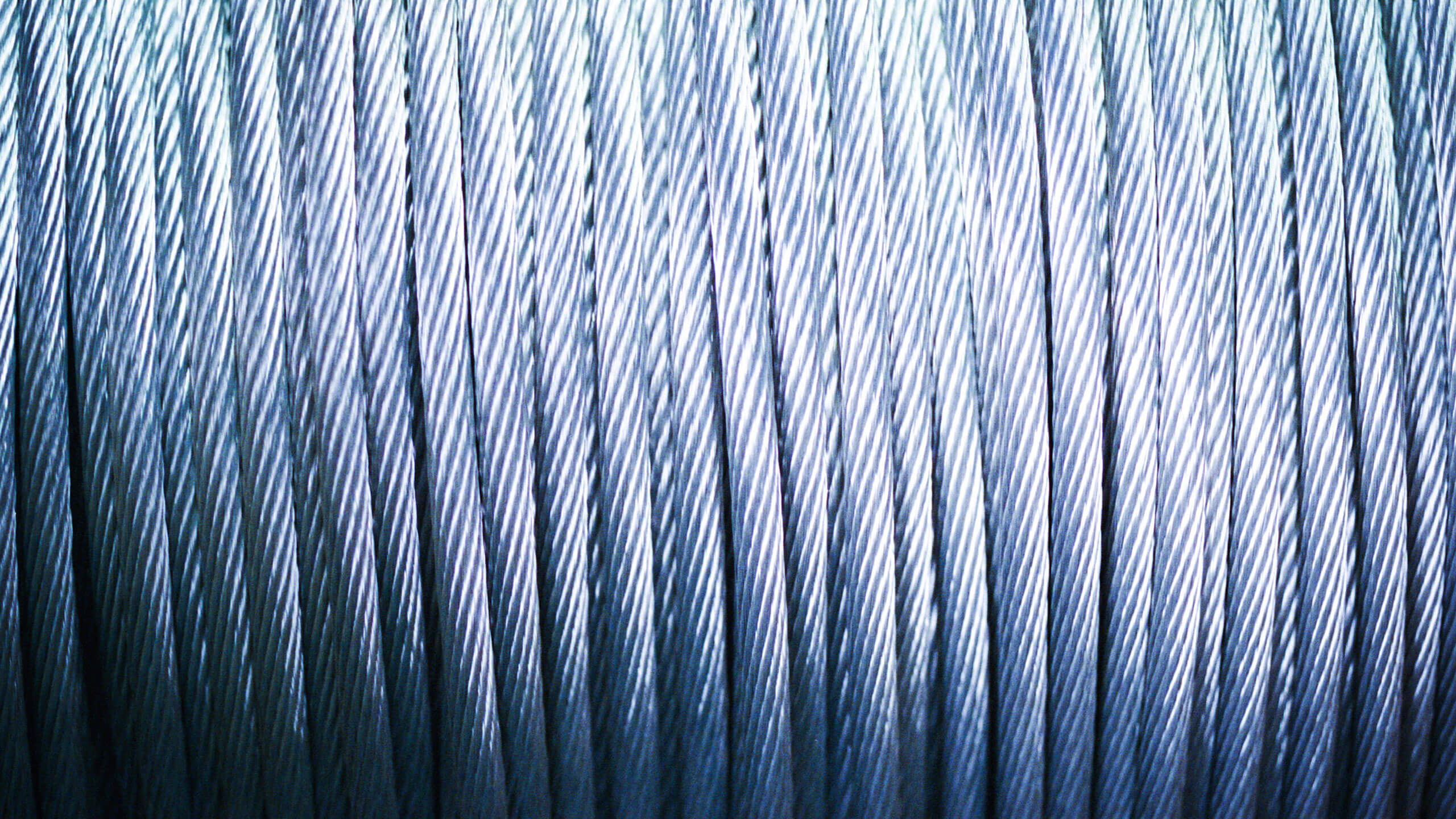

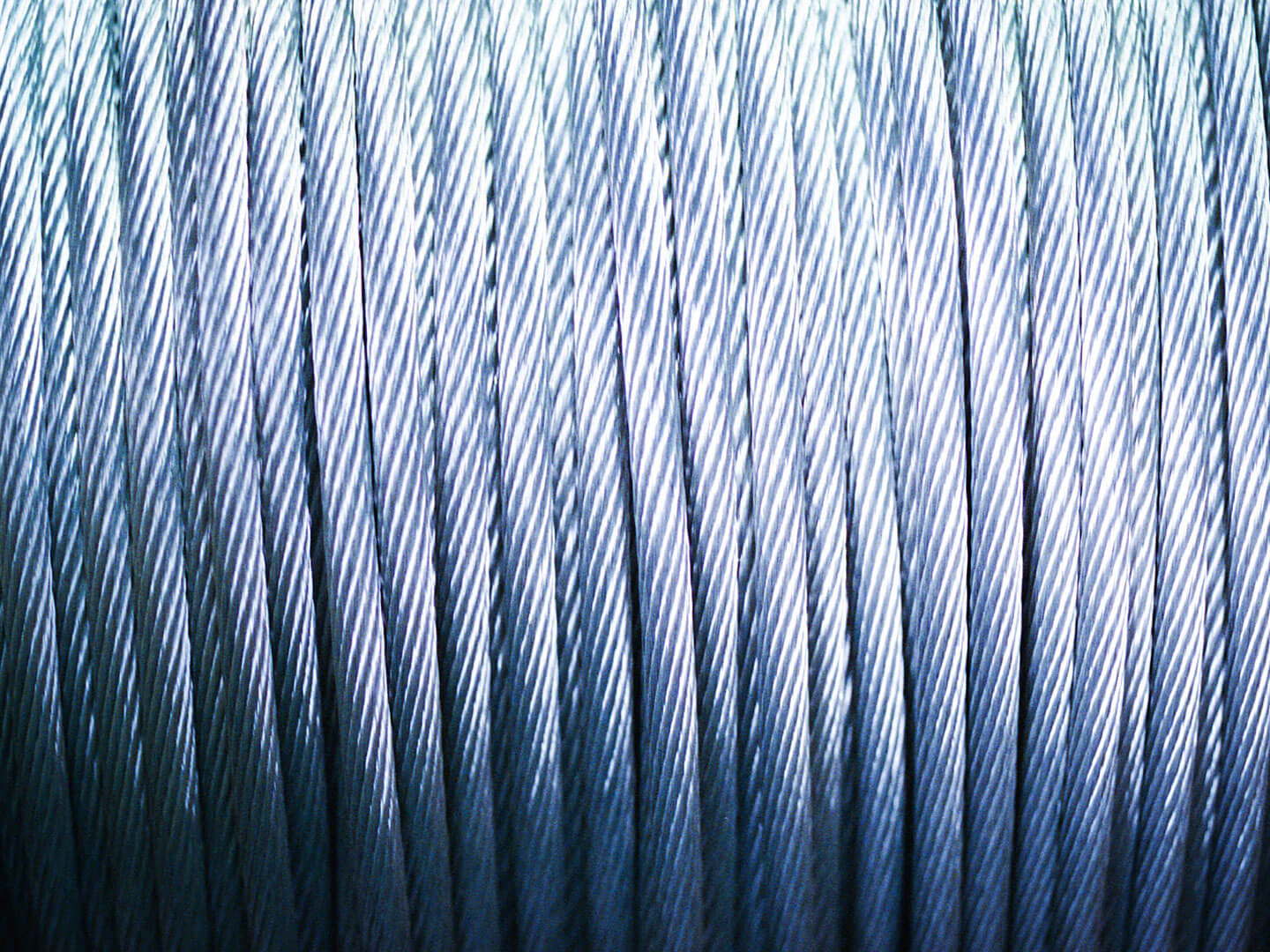

Mr. Kobayashi: All those machines with the wires in them are essentially weaving things from threads of metal. They weave and twist and bundle all the metal threads into products. They may become electrical wires, harnesses, or other types of products depending on how they are woven or twisted.

By “electrical wires,” do you mean the electrical wires we see hanging from electric poles around town?

Mr. Kobayashi: That’s right. More broadly, you can think of them as metal wires that carry electricity. It could be anything from the long, thick cables used at a power plant, to the electric cable used to plug in a machine.

When you say “harness,” I imagine the cables that run all through the inside of a car.

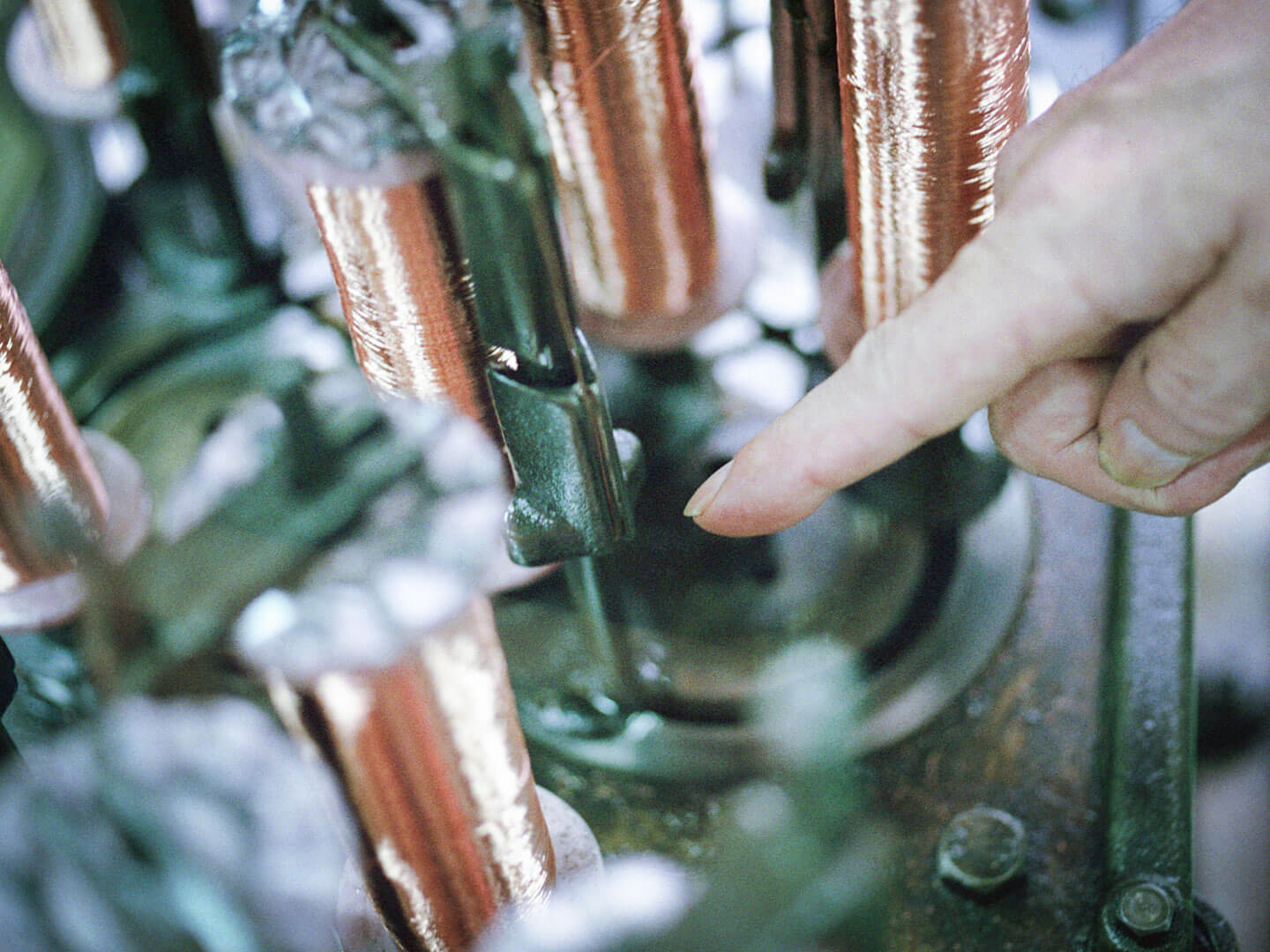

Mr. Kobayashi: Precisely. We weave them to be broad and flat, and hollow on the inside. That way they can withstand bending and vibration. Originally we made them to be electrical wires, to conduct electricity inside a machine. We weaved them tightly so they wouldn’t stretch or compress. But now they are less like electrical wires, and more like shields. We run an electrical wire through the hollow center, and block the electromagnetic waves the wire emits. Since we have to run something through the middle, we weave it loose so it has elasticity. Once we had a new way of weaving it, we were able to use it in cars as a harness for the first time. We use the same machine whether we weave it tightly or loosely, but actually it’s more difficult to weave it loosely.

With the old, slow machines, you can’t just press a button and make something, but the user can bring their own skill and ideas to it.

It’s more difficult to weave it loosely? I think of Japanese manufacturing products as being highly detailed, sensitive, and accurate, so it seems like it would be a bigger deal to weave it tightly.

Mr. Kobayashi: I suppose people might think of it that way. I guess it was about ten years ago. At that time, we were still weaving everything tightly. But we got a request from a client that they wanted something looser. Since the machine was built to weave tightly, we had to proceed by trial and error. From the weights that pull the threads, to the height and width of the parts that gather the bundle of threads together, through repeated fine-tuning we created a new way of weaving.

I see. When you weave something tightly you just have to apply full power, but weaving it loosely requires more balanced strength.

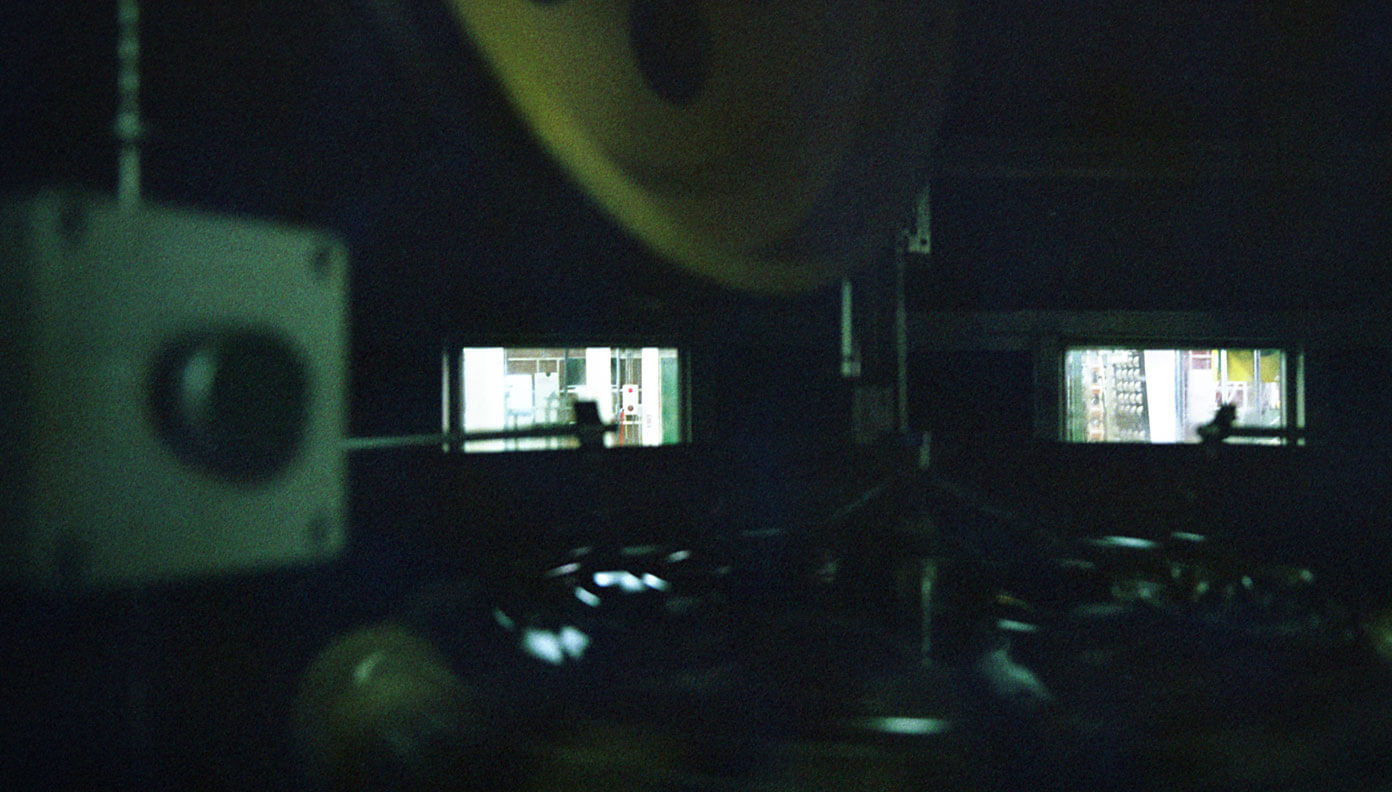

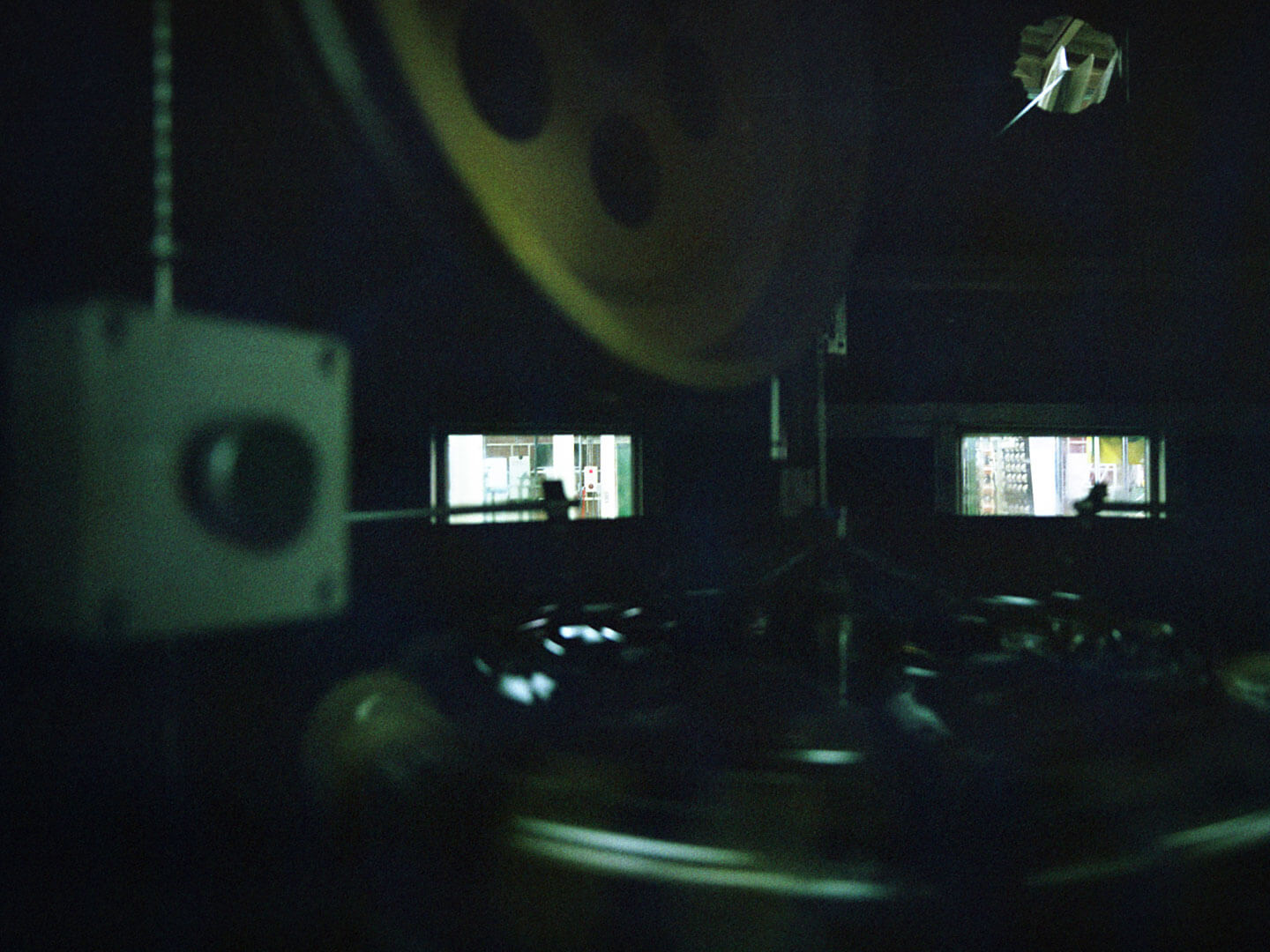

Mr. Kobayashi: That’s correct. That kind of subtle calibration is what our company specializes in. And that’s precisely why we continue to use older machines. With newer machines, you just press a button and they do everything for you. The operation is simple, and they make lots of units with precision, speed, and efficiency. But they also give you less flexibility. There aren’t many elements that you can adjust, and you can’t intuitively fine-tune them, so there are limits to what you can make. If we threw away the old machines and we were using the newest machines to mass-produce off-the-shelf products, we wouldn’t have been able to come up with this technique.

So the machines being analog is what makes subtle calibration and trial and error possible.

Mr. Kobayashi: That’s correct. The newest machines are certainly efficient, but the big companies already have a lot of them so it’s meaningless for us to compete. With the old, slow machines, you can’t just press a button and make something. But what’s good about them is that a skilled user can make adjustments and try ideas.

So you manufacture high-tech products, but you use old machines to do it. That’s interesting, because it seems contradictory at first. So does that also mean that it takes artisanship to operate the machines?

Mr. Kobayashi: That is also true. We have our veteran operators use the old machines. They’re old and analog, so each machine has it’s own quirks and differences.

When the same machines are all slightly different, they must be hard to use without experience. That must also limit the number of people who can operate them.

Mr. Kobayashi: Of course we’ve compiled manuals of accumulated experience so that other people can refer to them when using the machines. Information about differences in product width, different gears, machine speed, etc. And we are constantly updating the manuals. If another big company could do it all our orders would go to them, so for now we are maintaining the originality of our methods (laughs). Once you’ve adjusted your settings you can leave the rest up to the machine, so where the technician’s skill comes into play is in the preparation leading up to the actual manufacturing.

When you’re at the factory, all you can do is figure out how to do it with the machines you have, and then make it happen.

So it’s in the preparations that the technician shows their skill. Many people at other factories have said the same thing. At Meiko Futaba, is there any particular person who stands out?

Mr. Kobayashi: Our department chief, Mr. Harigai. He’s a great example.

Mr. Harigai, what is your specific job here?

Mr. Harigai: I keep track of which machine is operating where, and I monitor them. I also help people if they have questions concerning the site, and handle problems, like when a wire has snapped or something.

So you’re like a site director? When do you most feel like you’ve accomplished something in your work?

Mr. Harigai: Hmm. The job itself is very repetitive, so it’s hard to talk about “accomplishments.”

So you don’t feel much sense of accomplishment? (Laughs)

Mr. Harigai: Maybe when I am able to fulfill a client’s wishes.

So they must have some difficult wishes?

Mr. Harigai: Sometimes they ask for really crazy things. But you know, it’s a factory. All you can do is figure out how to do it with the machines you have, and then make it happen.

You’re very frank(laughs). But I guess that’s what a technician has to be like. Are there any things you’re particular about when you manufacture something?

Mr. Harigai: Particular? That’s a hard one too (laughs).

I think of technicians as being very particular, but is that not correct? (laughs)

Mr. Harigai: If I had to say, I guess it would be that I won’t distribute bad products.

You really are a frank person (laughs).

Mr. Harigai: Really? Well, I guess that’s how it is (laughs).

Mr. Kobayashi: Mr. Harigai talks like it’s no big deal, but it takes serious technology to weave a 50-micron metal thread without cutting it. Not anyone could do it. I was hoping when you interviewed him that I’d get to hear what makes a good or bad technician, or manufacturing tricks, but he won’t tell us (laughs).

Yes, he really doesn’t tell us much (laughs).

We don’t like to stand out, but we are quietly proud that our products are used in so many high-tech products.

Mr. Kobayashi: Since I’m on the factory operation side they’re very important points to me...but maybe those high-tech manufacturing methods don’t seem so difficult to him. That’s why human resources training is such an issue for our company (laughs).

A lot of technicians are the type to tell you to learn by watching, aren’t they? Aside from human resources training, is there anything else that you have to be mindful of, at the factory or in the company in general?

Mr. Kobayashi: People in our industry don’t like to stand out, but we are quietly proud that our products are used in so many high-tech products. So in order to increase all of our employee’s motivation, we tell them how the product they are making will be used.

It must be important to know how your work and effort is affecting society at large.

Mr. Kobayashi: But it’s not like our employees brag about it to other people. They seem to be satisfied by just thinking to themselves that “this machine is working because of something I made.” (Laughs.) They’re objective about it, but they also have pride and passion.

INDUSTRIAL JP has shown the world your employees’ hard work in the form of a music video, is that all right? (Laughs.)

Mr. Kobayashi: We see the same machines all the time, but they’d never seen them look so cool, so we were really surprised. However many times I see it, I can’t believe those are our same machines. The person at INDUSTRIAL JP said this too, but sometimes it can be a good thing to show work that is usually unseen.

FACTORY

meiko futaba

Meiko Futaba Co., Ltd.

Founded 1954, Meiko Futaba has manufacturing centers in Ibaraki, Yamanashi, and Iwate prefectures, as well as Guangdong, China. Their main products are electrical wires and harnesses. Their electrical wire division turns metal wire into threads, and twists and weaves them to create everything from power cables for electrical devices, to power lines for towns and power plants, to harnesses for use inside of cars.

Ibaraki factory: 6140-1 Onogomachi, Joso-shi, Ibaraki Prefecture