INDUSTRIAL JP

idstr.jp open shareApril 21, 2025

AT-14

sobajima seikan

interview

Creating products that connect not only functional value

but also emotional value and culture.

// sobajima can factory interview

Sobajima Seikan Co., Ltd. is engaged in the manufacturing and sales of cans used for dried goods, confectionery, and other products. At its factory, located slightly away from Nagoya Station in Aichi Prefecture, the company produces a variety of cans, including round and square cans, ranging from ready-made to fully custom orders, to meet a wide array of needs. Founded in the Meiji era, Sobajima Seikan has been dedicated to cans for many years. Why do they insist on multi-variety production? We explored the background.

sobajima can sign

ID-13

sobajima can

takecha

We don’t want the entry point for orders to be “price” or “lot size.”

Even small jobs are part of Sobajima’s Culture.

We heard that Sobajima Seikan offers a wide variety of original design products and also accepts small-lot orders. Isn’t it unusual in can manufacturing to handle multi-variety, small-lot production?

President Ishikawa: Cans are made using dedicated mass-production equipment. The basic principle in the industry is “to produce large quantities using machines that can only make cans.” The problem with that is that differentiation often comes down to “pricing.”

Of course, there are other ways to differentiate, such as using unique materials, but the entry point for orders is still often dictated by price. As a mid-sized company, Sobajima struggles to leverage economies of scale for low-cost mass production. Instead, we have built a system that utilizes our long-cultivated expertise to handle small-lot orders and accommodate a wide range of shapes and sizes, including square, round, and oval cans.

Producing various types of cans seems to complicate the production process and impact efficiency. How do you handle this?

Ishikawa: By utilizing surplus equipment for dedicated production lines and improving mold changeover speeds for our technicians, we keep some of our products in stock, enabling us to start manufacturing immediately upon receiving orders. This approach allows us to accept small-lot orders while maintaining short delivery times.

Our main products are colorful cans, which usually require a minimum order of 3,000 units. If a customer says, “I want a red can,” but the minimum order is 3,000 units, it becomes a high hurdle for small confectionery businesses.

So, you manufacture products in advance to meet such needs?

Ishikawa: Exactly. There is a risk in producing items without knowing if they will sell, and warehouse management is necessary. But ultimately, it all starts with customer orders. Taking on small-lot jobs has always been part of Sobajima’s culture.

Precision handwork down to 0.01mm.

A complex process requiring not just experience but also intuition and skill.

Sobajima Seikan seems to handle the entire manufacturing process in-house. What are the key steps involved in can production?

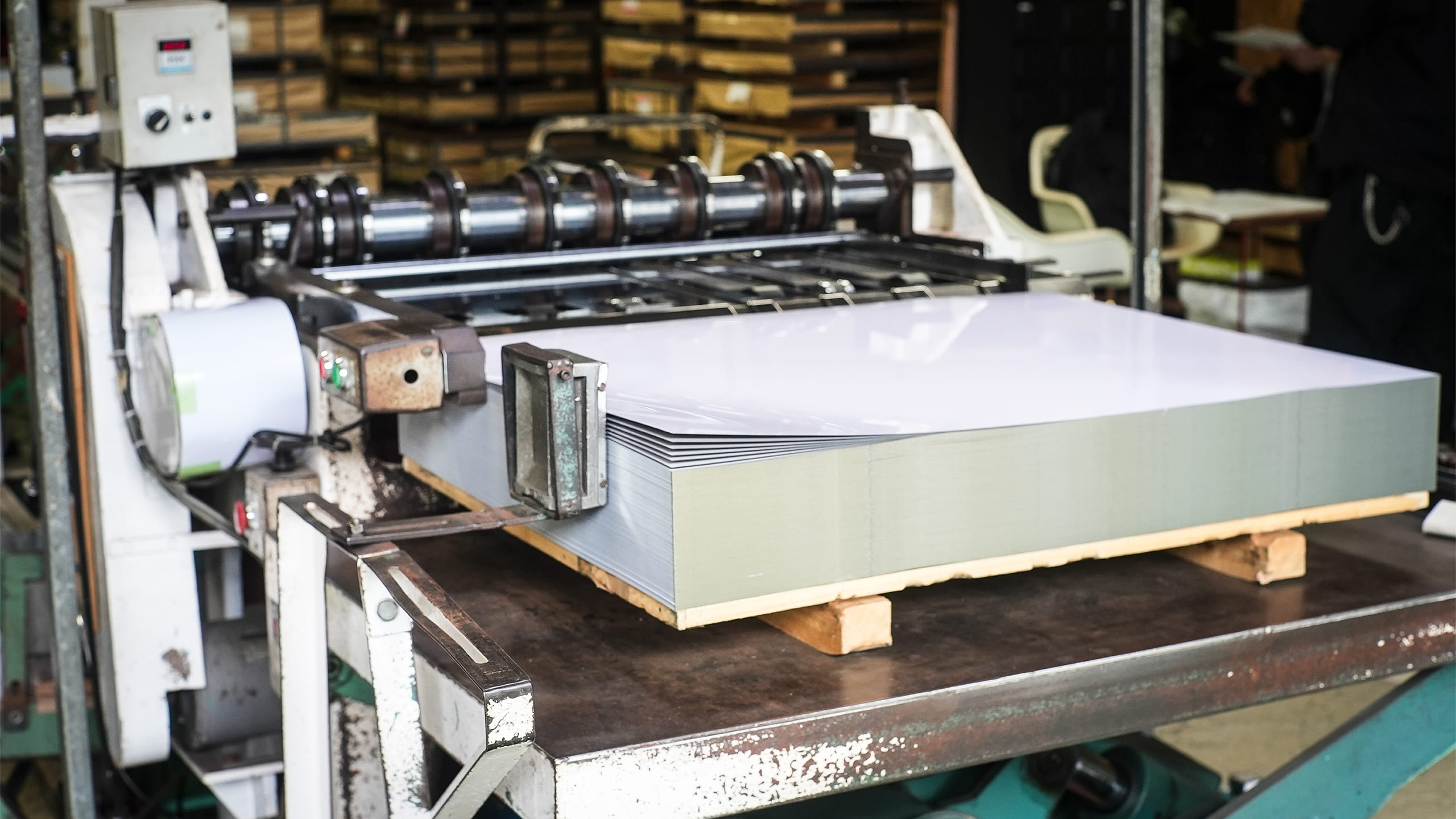

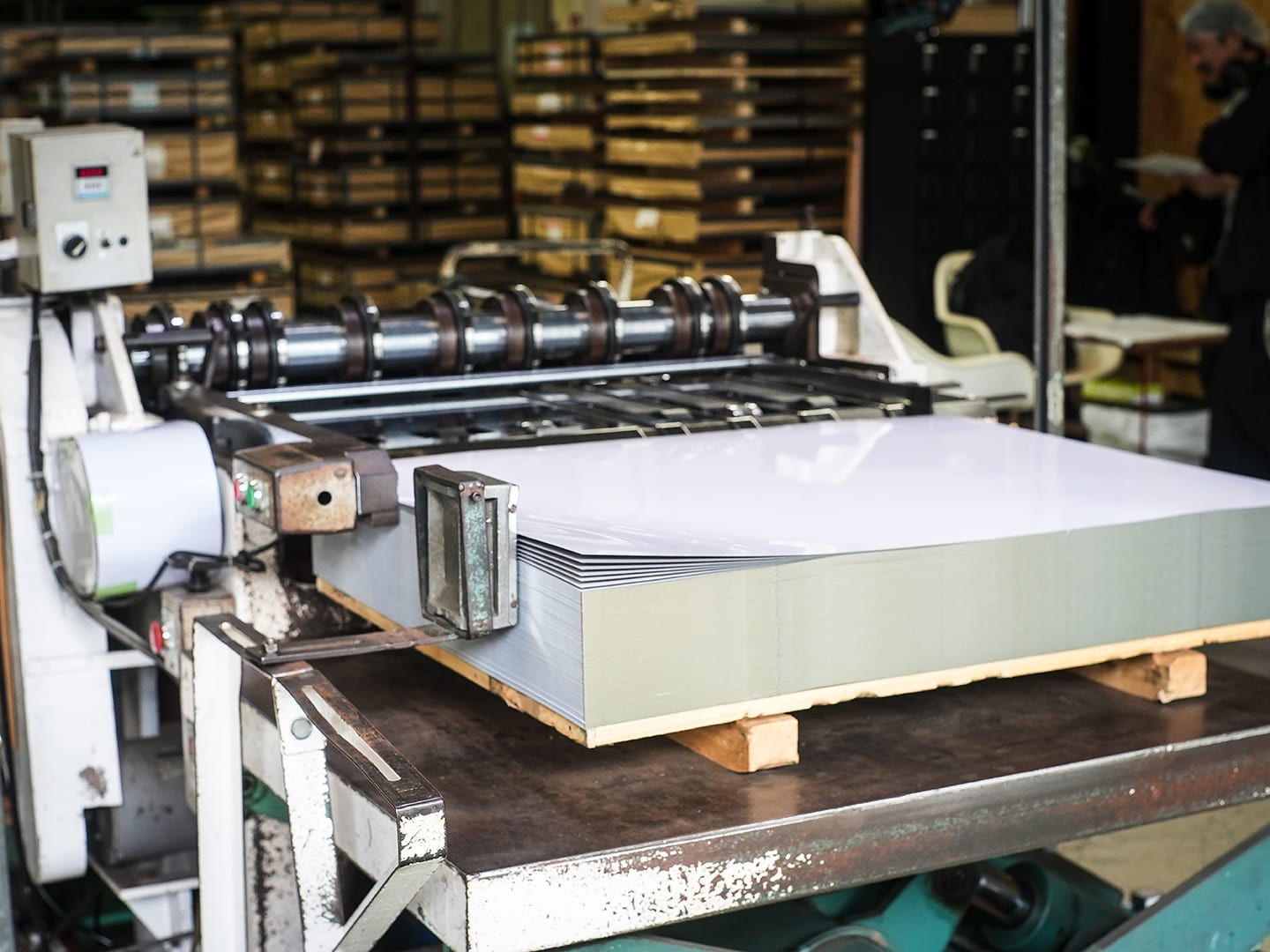

Slitting Process – Iwamura: The process involves cutting, pressing, and line processing, followed by inspection and shipping.

The initial cutting is done with a machine called a slitter, which divides the steel sheets into three parts: the body, lid, and bottom of the can.

The steel sheet is manually set into the machine, measurements are checked, and the machine width is adjusted manually to change the cutting width. This requires meticulous adjustments down to 0.01mm, and the process is done manually. The condition of the machine and the characteristics of the steel sheets also affect the process, making it more complex than it may seem.

It sounds like a process that requires a high level of craftsmanship.

Iwamura: I’ve been working in slitting for 25 years. Without experience, it’s hard to understand what to watch out for. It takes time to develop the ability to adjust for machine conditions and steel sheet characteristics. Intuition and skill also play a role.

What is the most important aspect of the cutting process?

Iwamura: Preventing scratches on the steel sheets. The edges, called “burrs,” can be jagged, and if the sheets rub against each other, they can get scratched. A scratched sheet becomes unusable, so we manually feed the steel sheets into the machine to avoid this.

The sheets look thin, but how heavy are they?

Iwamura: They are about 0.2mm thick, similar to a strand of hair, but each sheet weighs about 1kg. The trick is to introduce air between the sheets as they are fed into the machine.

Even a slight angle adjustment affects the cutting process, and if not done properly, it can cause scratches or misalignments that affect subsequent steps. Since this is a foundational process, ensuring smooth material supply is essential to keeping production on schedule. Balancing speed and precision is crucial.

Manufacturing relies on strong communication.

Small everyday interactions make it possible.

The initial process requires extreme precision. Handling multi-variety, small-lot production must significantly increase the workload. How do you manage this?

Iwamura: Manufacturing requires constant communication, even about minor issues. Although the factory is divided into different processes, it functions as a single production line, including the sales team. Close communication enables us to handle small-lot production.

It is also important to create an efficient work line based on the number of processes.

However, simply being able to use machines is not enough.

That is both the challenge and the fun of it.

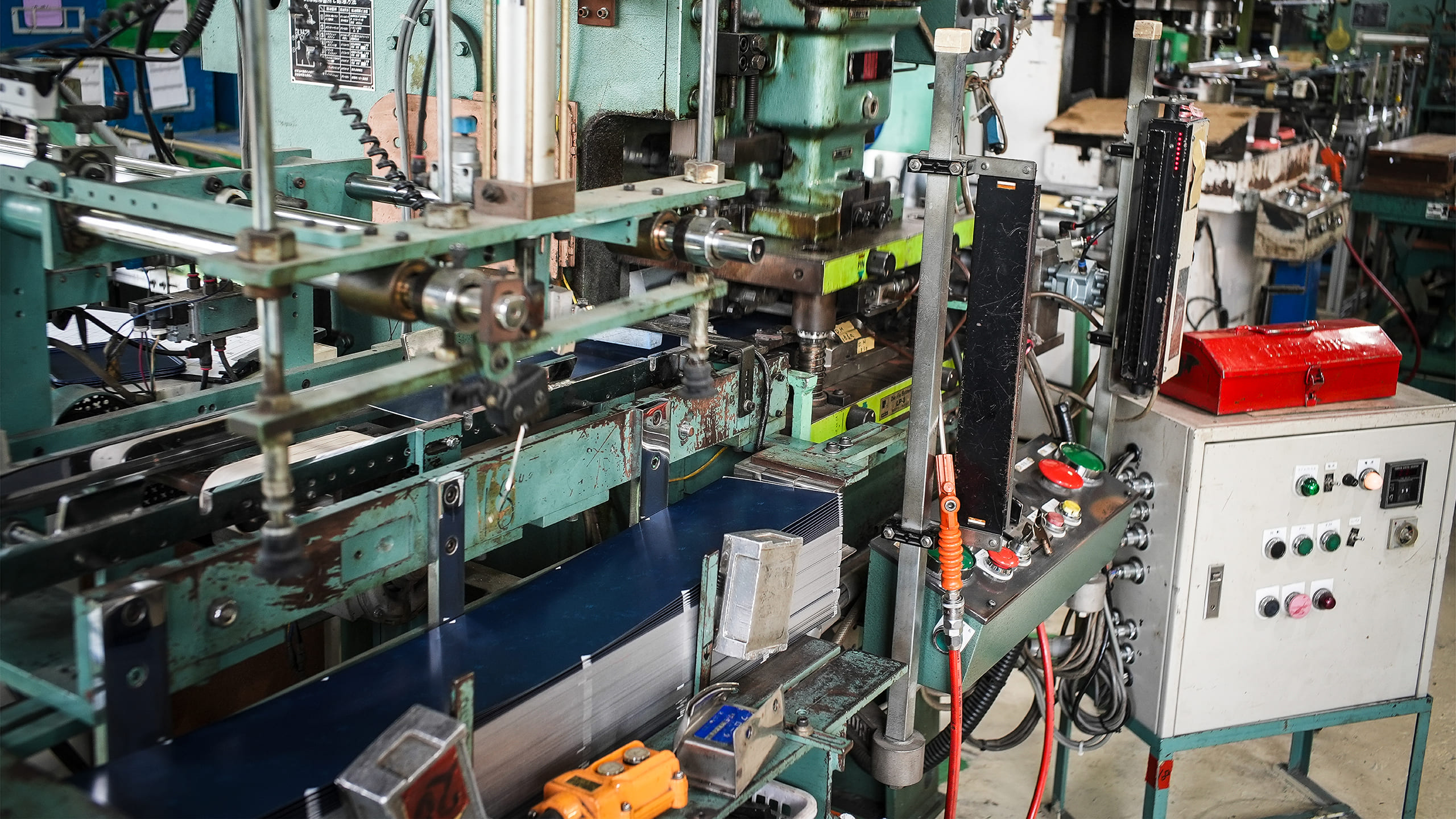

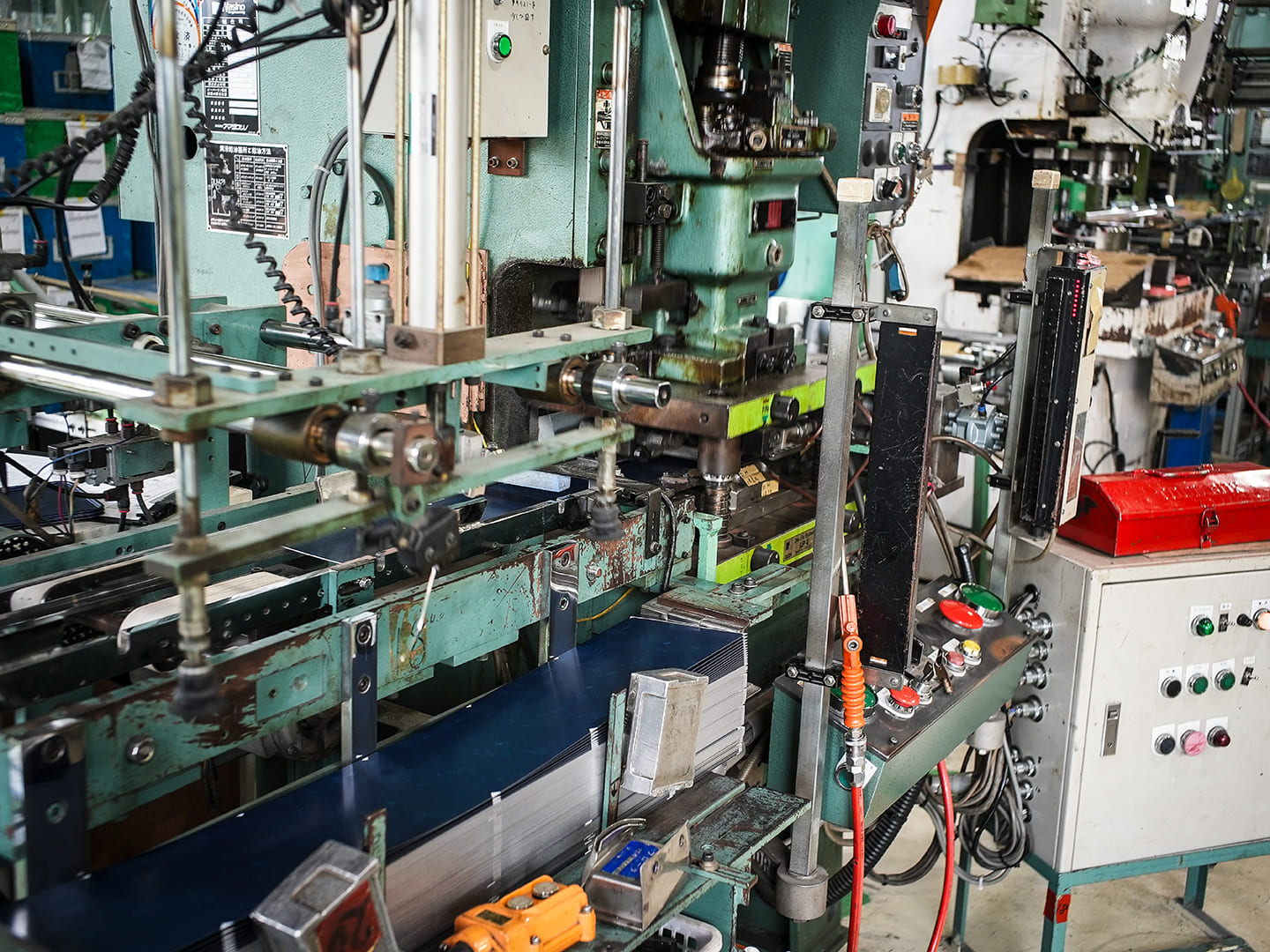

After the steel plates are cut in the cutting process, they move on to the pressing process. I was surprised by how many pressing machines are in operation. How is the work structured?

Pressing Department - Hotta: We have over 20 pressing machines with pressures ranging from 25 to 80 tons. Sometimes, we use cranes to move the pressing machines and reconfigure the work lines.

So you can flexibly change the production line depending on the work content?

Hotta: Exactly. The number of pressing steps varies depending on the task, so we move pressing machines around and even transform the setup into an assembly line when needed. That’s why the pressing area can look completely different every time you visit! (laughs) I think we might be the only company in Japan that regularly moves pressing machines around as part of daily operations.

In the pressing process, how do you shape the cut steel plates into the “body, lid, and bottom” of the product?

Hotta: For the lid, we use a method called “deep drawing,” which forms a seamless three-dimensional shape from a single flat sheet. The amount of stretching can vary depending on the material and printing type. To ensure consistency in the drawing process, we set up automated machines carefully.

At Sobajima, we manufacture cans in a wide variety of colors and shapes. This means we have to memorize hundreds of different molds while also mastering machine operation. But simply knowing how to use the machines isn’t enough. That’s what makes it both challenging and enjoyable.

Work shouldn’t be driven by evaluation.

A bold organizational change to a "Teal organization"

Watching the manufacturing process, it’s clear that multi-variety, small-lot production requires not only skill and effort but also a significant communication cost. Even though this culture is well-established, what’s the key to sustaining it?

Ishikawa: Motivation has been a big factor. Previously, our company functioned like an “extremely top-down subcontractor,” where employees were simply told what to do.

When I returned five years ago, harassment and overwork were common. Employees secretly worked overtime because they would be scolded if caught, essentially working non-stop.

Meetings and morning assemblies didn’t exist; people would just go to their stations without greeting each other and work through the day.

That’s a stark contrast to the atmosphere at the factory now, where everyone greets each other politely. How did you change the internal culture?

Ishikawa: Even though employees “only did what they were told,” they had a culture of self-reliance, stemming from unclear instructions like “do it properly.” To build on this, we adopted a “Teal organization” model and introduced a self-reported compensation system.

Traditional evaluation systems weaken autonomy, as people work for ratings rather than purpose. Instead of increasing pay based on top-down evaluations, employees set their own goals and assess their achievements themselves. Salaries are given upfront as an investment, and employees prove their value independently. We eliminated rankings and management structures, and I even abandoned the title of “president.”

Ishikawa: Since we don’t have official titles, it feels like we just have various groups or circles. There’s a manufacturing circle, a design circle, and a sales circle. In some circles, I’m a leader, but when I go to another circle, my position and role completely change.

Currently, I don’t give orders or instructions. Instead, I trust each person’s autonomy and ask them to think about production. Compared to the time when I used to yell at people to get things done, now, meeting times, production output, and sales have all increased, and I believe our productivity has improved overall.

How did your sense of organizational transformation come about? What experiences shaped this?

Ishikawa: Well, I’m not sure. But originally, after graduating from university, I worked in the financial industry for about 10 years. During that time, I saw many different companies, and what I noticed is that successful companies have employees who genuinely seem to enjoy their work. It’s not about them doing things because they’re being yelled at, but because they work with enthusiasm and their own will. I realized that was really important.

Whenever I visited a good company, the employees were always friendly and willing to talk. They’d greet you with things like, "Hello," or "How can I help you?" and it felt natural.

On the other hand, in companies with a poor atmosphere, employees would just glance over and say "Someone’s here." When you look closer, those companies don’t tend to perform well.

I truly believe that companies where people are happy to work are better companies. More than anything, when I thought about leading my own company, I didn’t want a situation where I was just enriching myself while everyone else struggled. That would make me feel unworthy of calling myself a manager.

I believe the ideal situation is that everyone works following their conscience, and as a result, it benefits customers, society, and leads to sales and profits. It might sound like an idealistic view, but the moments when I see that kind of management is possible because I trusted everyone and entrusted them with responsibilities, that’s when I’m the happiest.

So, I let go of any privileges that come with being a manager. I don’t give orders or force anyone to do anything. I’ve let go of all of that, and I trust everyone, delegating responsibilities. I hope that by taking on the risk and showing them that I’m entrusting important things to them, it will inspire them to live autonomously.

The only thing I can do is make decisions with conviction.

I’ve stepped away from titles and now focus on the importance of the process of “doing it together”.

There must have been significant organizational changes from the previous generation. Was there any resistance or tension during this transition?

Ishikawa: The organizational transformation didn’t start when I became the president. When I returned in 2020, the company was almost in a "no turning back" situation, and things weren’t looking good.

At that time, I wasn’t even in an official position, but I told the previous president that I wanted to take over the management of the company. Since then, I’ve continued to work from the same position I’m in now. So, it wasn’t that I suddenly became the president and changed everything overnight. It’s been more of a gradual change over the past 4–5 years.

Of course, there have been various reactions, and unfortunately, some people left. It was a tough time for everyone, and there were conflicts. But there was always this underlying understanding that “we have to change someday” and “we can’t continue like this.” Most of the team, despite the ups and downs, have overcome many obstacles, and now we’re all focused on moving forward together.

While some aspects of the change may have been drastic, the process of "building it together with everyone" has been repeated throughout. Because of that, I believe that everyone feels this is not someone else’s business but their own company, and they are focused on what to do with it.

For example, when we created our Mission, Vision, and Values, it wasn’t something I decided on by myself. If I had just said, "This is our Mission, Vision, and Values! This is what we’re going to do!" it would have been a top-down approach.

Instead, we created a project team with everyone, and we worked together to figure it out step by step, learning as we went.

I just helped facilitate by writing things down. I’d say, “I think this is what everyone’s trying to say, but what do you all think?” and repeated that process. By the time we finished, everyone recognized that these were the promises they had decided on themselves.

The closeness of “doing it together” seems to be a key theme in the organization’s transformation.

Ishikawa: I’ve let go of the title of president, and I’ve also given up all the privileges and authority that come with it. I don’t do anything using the power of the president. I don’t even have any say in decision-making, which I think is a good change because it allows things to move forward quickly.

I’ve made it possible for everyone to see how the expenses are being used, and I’ve allowed people to freely use the company credit card for things like Amazon purchases.

Since I’m not doing anything with special privileges and everything is transparent, I think that’s helped build a trusting relationship with everyone.

Honestly, I think it’s quite incredible that the organization has changed so much in just 4–5 years.

Ishikawa: We had to change. Of course, I’ve made plenty of mistakes. I had no experience in management, I was a beginner in manufacturing, and I knew nothing about leadership or projects. I was completely inexperienced.

What I could do, though, was make decisions with resolve. I realized that taking on risks was the only thing I could do.

I’m sure everyone sees how you’ve been willing to shoulder those risks, and it’s clearly communicated to them.

Ishikawa: I’ve been studying every day for the past four and a half years, and even now, I come to the company earlier than anyone else. I do have a family, so I sometimes leave early, but I’m still working from home after that. I think everyone sees that I’m putting in that effort.

Recently, something that made me really happy was when the team organized a Family Day on their own.

Family Day is when employees bring their families to the company to show them where they work. Families can say things like, "This is a good company," or "This is where you work," and it’s wonderful to hear that. I never would have imagined that happening 4–5 years ago.

If you don’t have a sense that "this is a good company," you wouldn’t organize something like that. So, it made me really happy that everyone was able to make Family Day happen with that kind of mindset.

Labor shortages and aging equipment…

the challenges facing the manufacturing industry and the future of human resource development at Sobajima Seikan.

Sobajima Seikan has undergone significant changes, but what are the issues you hope to address going forward, and what challenges do you see in Japan’s manufacturing industry?

Ishikawa: There are many issues, but from an industry-wide perspective, it’s definitely labor. I think we’re relatively good at hiring, but we’re still far from fully staffed.

In Aichi Prefecture, especially, the automobile manufacturers and parts suppliers are dominant. It’s common for them to offer bonuses of 8 months’ salary. So, when comparing just salary, it’s tough because people often prefer to go there.

Our company, due to its long history, is also dealing with aging equipment.

We need to update our equipment, but the question is where to find the funds. Even if we replace it with something new, it won’t necessarily lead to a big increase in productivity. For example, even if production speed doubles, we might not be able to keep up with the inspection process.

If it’s mass production with a single product type, then large lot automation works well. However, for small-lot, multi-product production, we have to set up each time. Even when automating with machines, the setup for automation is also necessary. In that case, we often rely on manual work to maintain speed.

Indeed, this is a field where flexibility is essential, so it’s not possible to rely entirely on machines.

Ishikawa: It’s definitely an area where flexibility is required, and we can’t just rely entirely on machines. There’s still room for improvement, but we haven’t really invested in personnel training or “people”. When new employees joined, there was no training—they were immediately put on the production line. From their first day until now, it’s been entirely on-the-job training (OJT) (laughs).

For the past 20 years, we’ve been in a kind of “lost era.” Some employees have been here for 20 years without ever studying or training even once.

Still, in recent years, people have started stepping up—taking certification exams, studying, and pushing themselves. Many didn’t even know how to study at first, but now some have earned multiple certifications through their efforts. The idea that “we have to change, we need knowledge to move to the next stage” has gradually spread. Recently, employees have even started organizing weekly study sessions to prepare for certifications, learning from each other. Considering that there was never a study culture before, I think this is truly remarkable.

In manufacturing, if we don’t properly study industry practices and quality control, we’ll only be doing temporary fixes when complaints arise. If we only apply short-term solutions, the same complaints will keep happening. That’s why we’ve decided to stop relying on quick fixes and instead work together to build real problem-solving skills.

Becoming a chosen company:

What it takes to build appeal.

You mentioned that Sobajima Seikan is still able to recruit, but looking at your social media, I noticed posts that focus on individual employees, which suggests a strong effort in this area. Is this something you’re actively working on right now?

Ishikawa: Yes, exactly. We need to become a company that people choose. If the company itself lacks appeal, no one will pick us. Without an initial touchpoint—like seeing us on TV or hearing about us—people wouldn’t even know who we are. If they can’t imagine what we make or how we make it, they’ll just think, “Well, working in the auto parts industry seems more stable.”

You’ve also been participating in markets and proactively increasing your external presence.

Ishikawa: To build social credibility, I see public exposure as one of my important roles. That includes appearing in media and giving lectures.

Nowadays, whenever something piques your interest, the first thing you do is look it up online. Media appearances leave a digital footprint, which may not directly translate into immediate sales or profits, but in the long run, they serve as valuable informational assets that contribute to our credibility in society.

Cans are eco-friendly that’s why it’s up to us

to lead the way in raising awareness.

Are there any unique initiatives that Sobajima Seikan is undertaking?

Ishikawa: The raw material for cans—steel—is actually highly recyclable. Steel has a recycling rate of about 95%, and aluminum is around 97%. In contrast, the global average recycling rate for PET bottles is only about 40%. We are producing environmentally friendly products and ensuring that all waste generated during manufacturing is collected and recycled.

I’m embarrassed to admit that I didn’t know that. A near 100% recycling rate is impressive.

Ishikawa: Most people don’t realize that cans are eco-friendly. That’s why we, as a company that produces one of the most consumer-facing steel products—cans—need to take the lead in spreading awareness.

At Sobajima, we manufacture ultra-eco-friendly, CO2-neutral cans using “Green Steel.” In simple terms, Green Steel is a type of steel produced with zero CO2 emissions. While it looks just like regular steel, we’ve fully adopted it for our Canday can series.

In fact, we were the first company in Japan to use Nippon Steel’s Green Steel, “NSCarbolex Neutral.” This means that our customers are contributing to CO2 reduction without even realizing it.

More than just sustainability:

The Artistic and protective value of cans.

You’re also putting a lot of effort into environmental considerations. It seems like there’s still so much to discover about the charm of cans.

Ishikawa: Moving forward, we want to ensure a stable supply of cans. From an eco-friendly perspective, of course, but also in terms of design. I believe cans have a strong affinity with art. If we use cans as a medium for packaging art, it allows people to keep a kind of miniature art piece in their homes for a long time—that’s a wonderful thing, isn’t it?

That’s true. Beautiful cookie tins, for example, often stay in homes for years. People even store letters in them.

Ishikawa: Cans have excellent moisture resistance and light-blocking properties, making them ideal containers for preserving important things. They help protect what’s precious.

For example, if parents store memorable things or records of their children’s growth in a can, it deepens their sense of love and care. At the same time, children can also feel how much their parents cherish their memories. We’re working on developing products that embody this concept.

Moving forward, we want to continue creating products that connect with Japanese sensibilities—things that convey quiet love, wabi-sabi aesthetics, emotional value, and cultural heritage.

FACTORY

sobajima can

Sobajima Seikan Co., Ltd.

Sobajima Seikan Co., Ltd. manufactures and sells cans used for dried goods, confectionery, and other products. The factory produces various cans, including round and square ones, from ready-made to fully custom orders, meeting diverse needs.

90-1 Tsukida, Nishijo, Ōharu-cho, Ama-gun, Aichi 490-1144, Japan

STAFF

who made this

Satomi Abe

Writer

Born in 1989. A web and social media editor for a fashion media outlet. Also works as a freelance interviewer and writer based in Tokyo, covering various fields such as music, entertainment, and business. Major publications include “Time Out Tokyo” and “Mynavi News.”