INDUSTRIAL JP

idstr.jp open shareJune 13, 2018

AT-8

toyokasei

interview

Generations coming together to

preserve a culture.

// toyokasei interview

Record sales are flourishing. As the transition from CDs to digital downloads and music streaming continues, many listeners are turning back to records for the joy of “owning” music. Many record factories have closed down, but we visited Toyo Kasei, which runs the largest record factory still operating in Japan.

toyo vinyl

ID-8

toyokasei

dj nobu

We made the Industrial JP track somewhat loud, and compensated by cutting out some of the low-end.

The word “press” is often used when making records, but your method is a bit different from the metal presses used by manufacturers like Shin Ei Industry. Can you tell us about your manufacturing process?

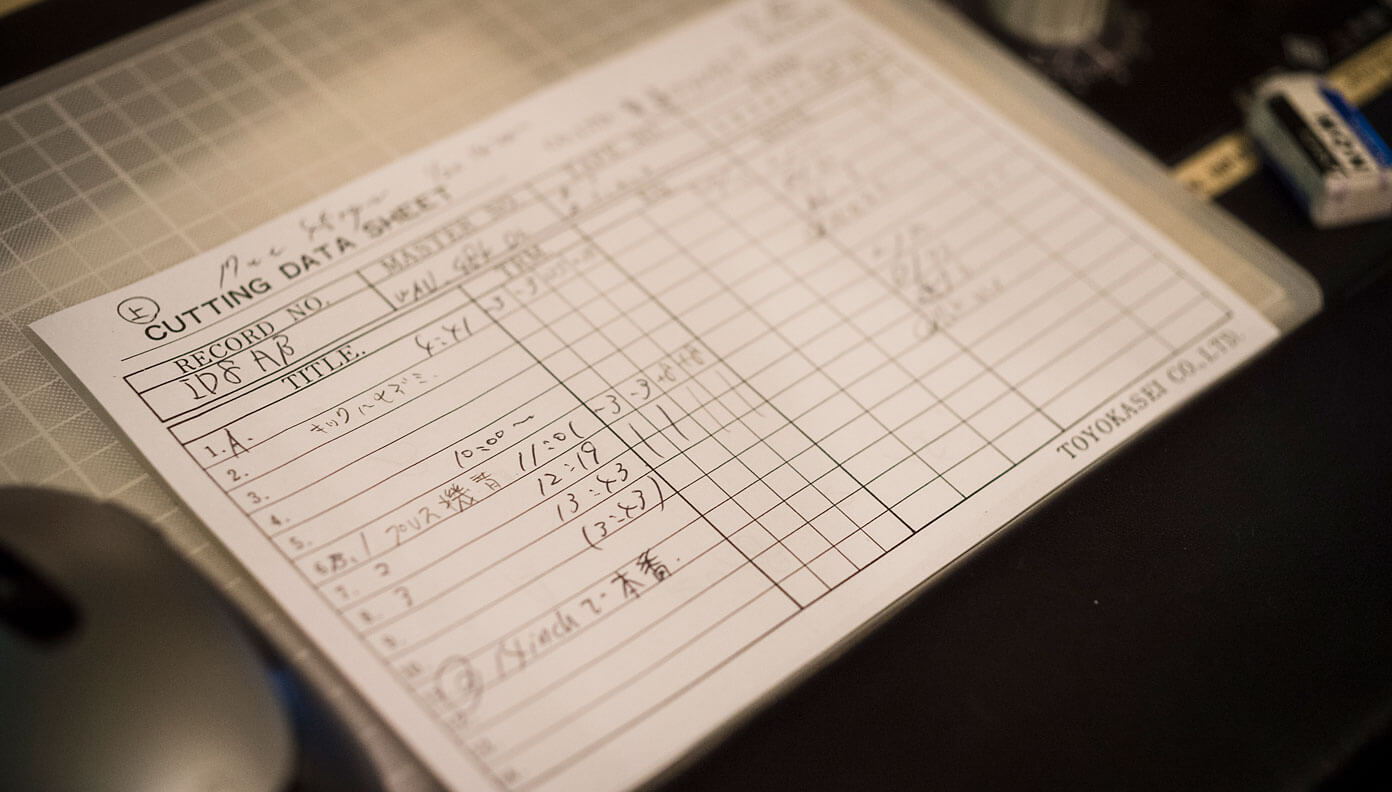

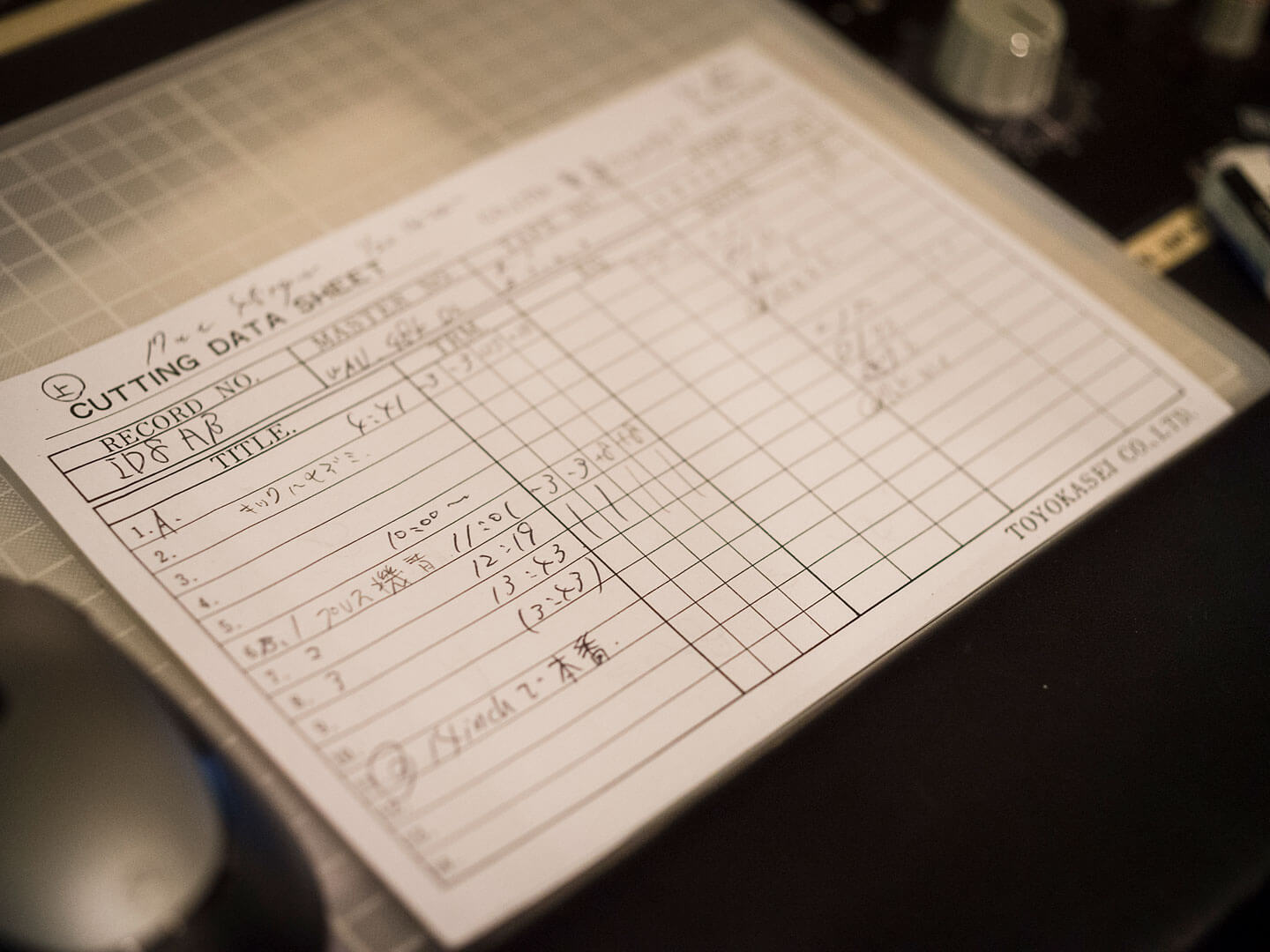

Totoku: Generally speaking, there are two steps to our manufacturing process. First comes “cutting,” when we make the lacquer disc for the master. Next comes pressing, which is the mass-production stage. This is the room where we cut the lacquer disc. These days tracks are generally produced digitally, and more than 80% of our customers send us their tracks in digital format. Of course, we can also receive tracks in CD form, as well as analog tape.

These days it’s standard to record and edit tracks using a DAW (digital audio workstation). Are there still any musical artists who record on tape?

Totoku: Of course there are some, but generally if we receive tracks on tape, it’s for a re-release of older music. It’s mostly classical music but sometimes rock too. Some time ago there was a trend of digitally remastering old music with an updated sound for re-release, but these days customers are more likely to want the records pressed with the original sound intact.

I see. Now that you mention it, there are a lot of re-issues at record shops.

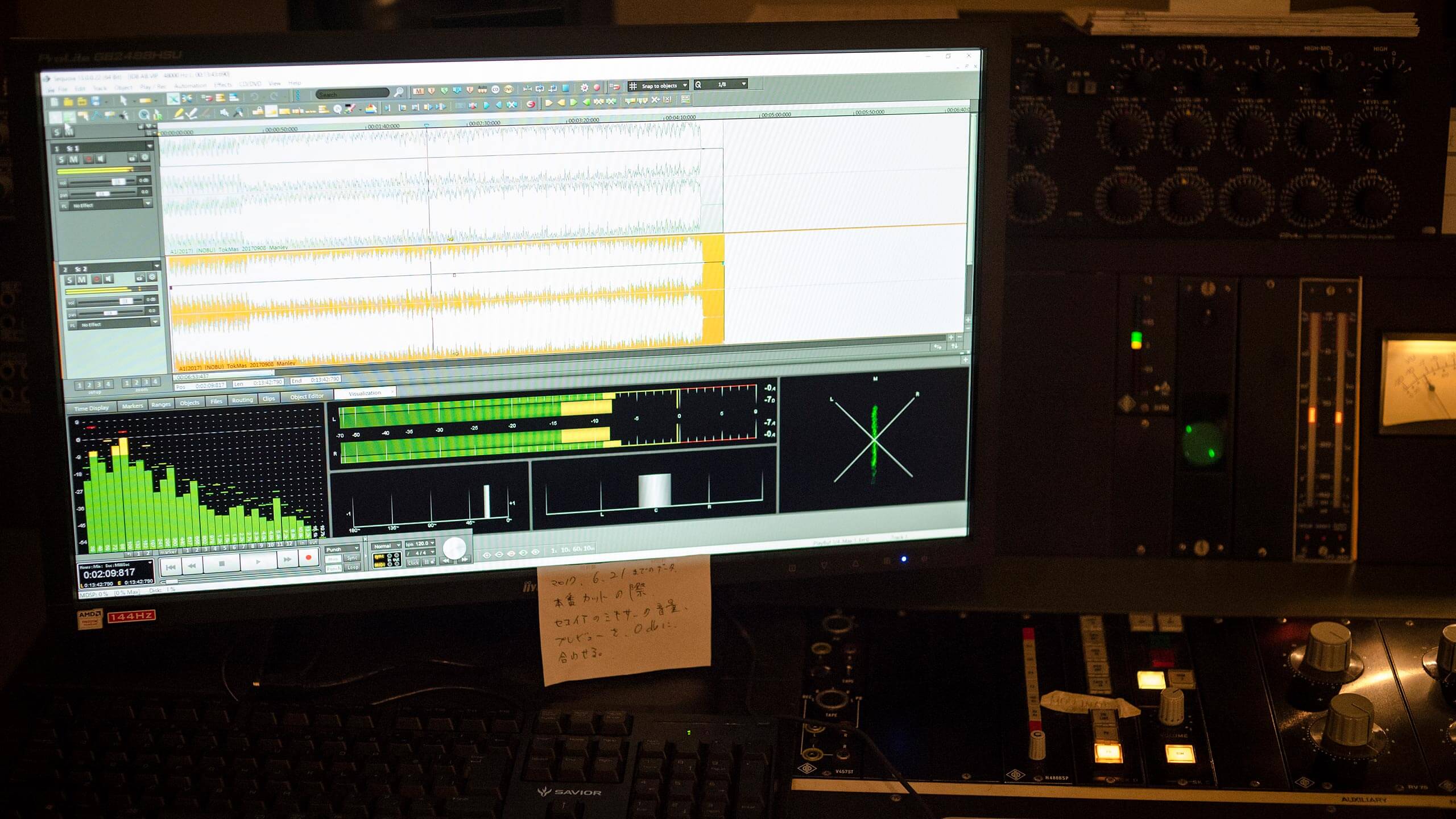

Totoku: We load digital tracks onto software called Sequoia, and adjust the EQ, volume, and sound quality for record pressing.

Are the original digital track and the one you use for record pressing quite different?

Totoku: They are. Some musicians even edit their tracks especially for vinyl. A record is a disc with a groove physically cut into it, so for longer tracks the space between the grooves has to be smaller. And with records, the needle follows the groove to physically produce sound. When the track is loud or the bass is strong, the vibration of the needle is bigger, which can lead to skipping or reduction in sound quality. So in the case of longer tracks or tracks with more bass, we make individualized adjustments.

This is the first time Industrial JP tried making a record. We also made an innovative music video. First we recorded the sounds of your record factory, and then DJ Nobu used those recordings to create the track. We they filmed the track being pressed onto records at your factory, and combined the footage with the track to make the video. What was your impression from the perspective of cutting a record using our audio material as a source?

Totoku: DJ Nobu’s track called TOYO VINYL was 4:40 on a 45-rpm 7-inch, which I felt is on the long side. So I made it somewhat loud, and compensated by cutting out some of the low-end.

I see. So a track just under five minutes is long for a 45-rpm 7-inch. That sounds like something you can only know from experience. Thank you for making it sound so great. What is the next step after you’ve adjusted the track?

Totoku: After we run the adjusted track through an amplifier, we use a specialized machine to apply the “RIAA Curve,” which suppresses the bass and brings out the treble. We use that adjusted track to cut the master.

What? You cut the master with the bass suppressed and the treble accentuated?

Totoku: That’s right. So when someone plays the record they’ll need a machine called a phono equalizer, which brings out the bass and brings down the treble. You can get a record player with a built-in speaker and and phono equalizer for about a hundred dollars. Turntables like the Technics SL 1200 that DJ’s often use don’t have phono equalizers. They use a separate mixer instead.

When you play a record with the volume all the way down you get a small crackling sound from the disc. Is the bass lowered and the treble raised on that too?

Totoku: Exactly. That sound is called “needle talk.”

Now I finally know where that sound comes from.

My ears aren’t as familiar with older music, but I understand more recent music better. The music you listen to does affect how you cut the record.

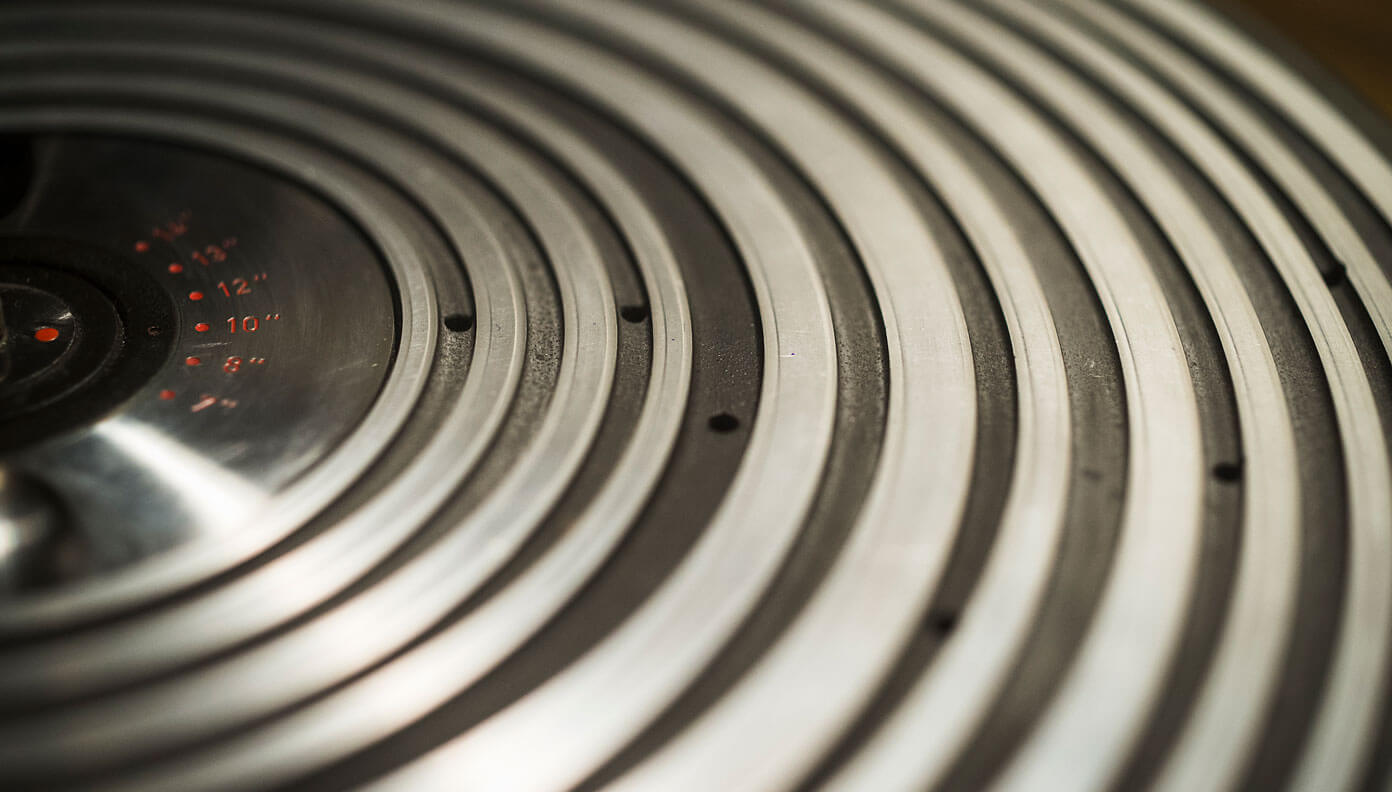

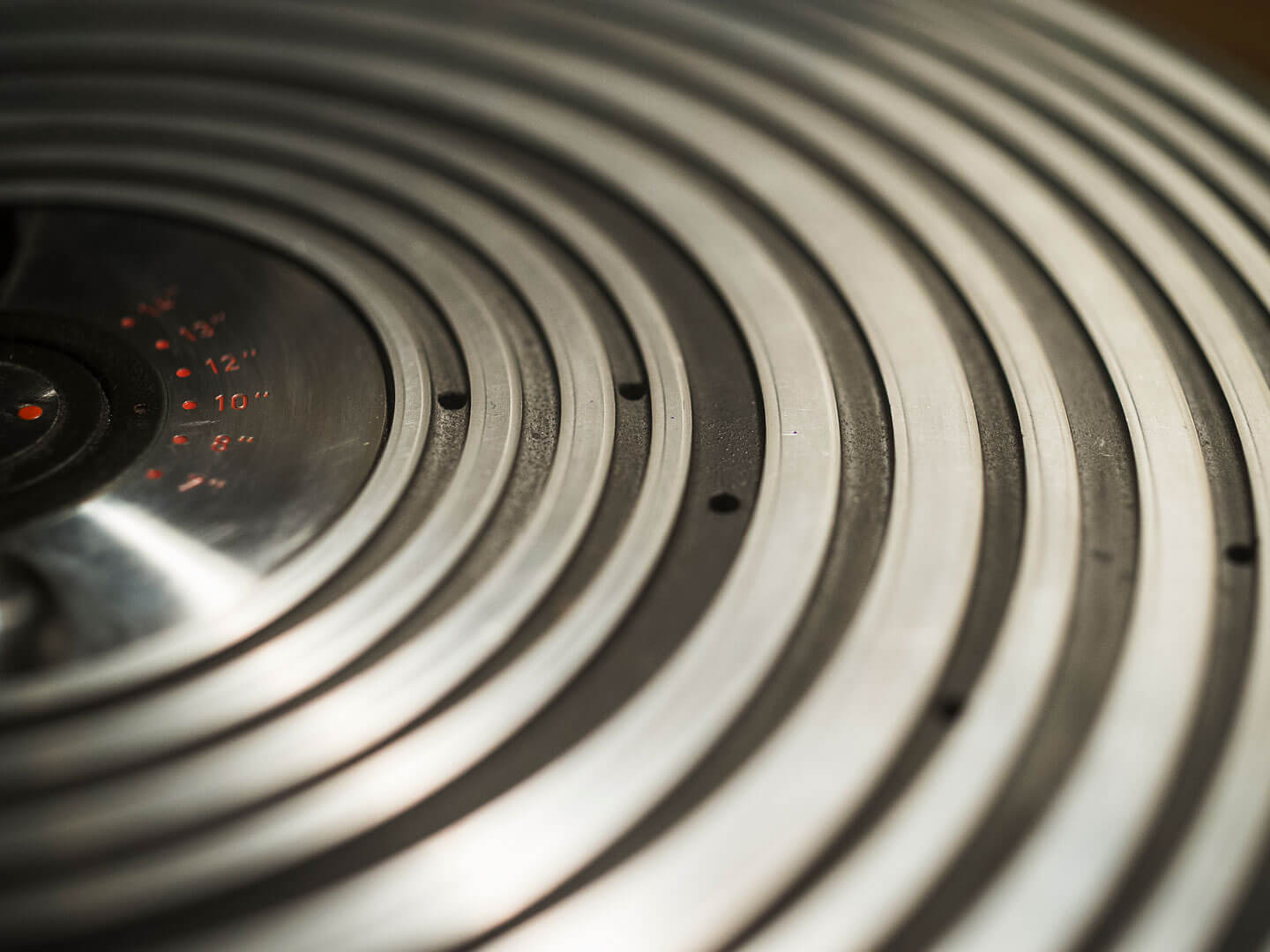

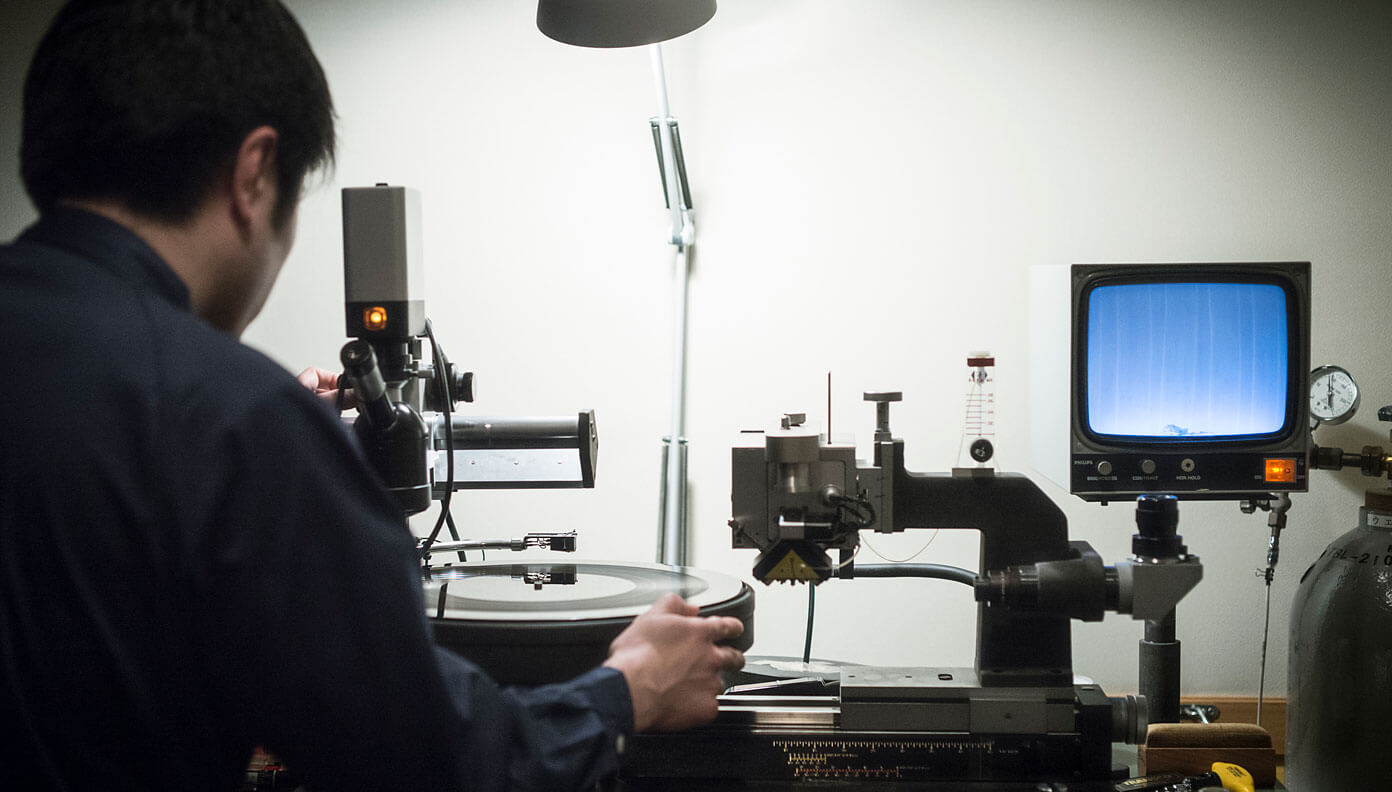

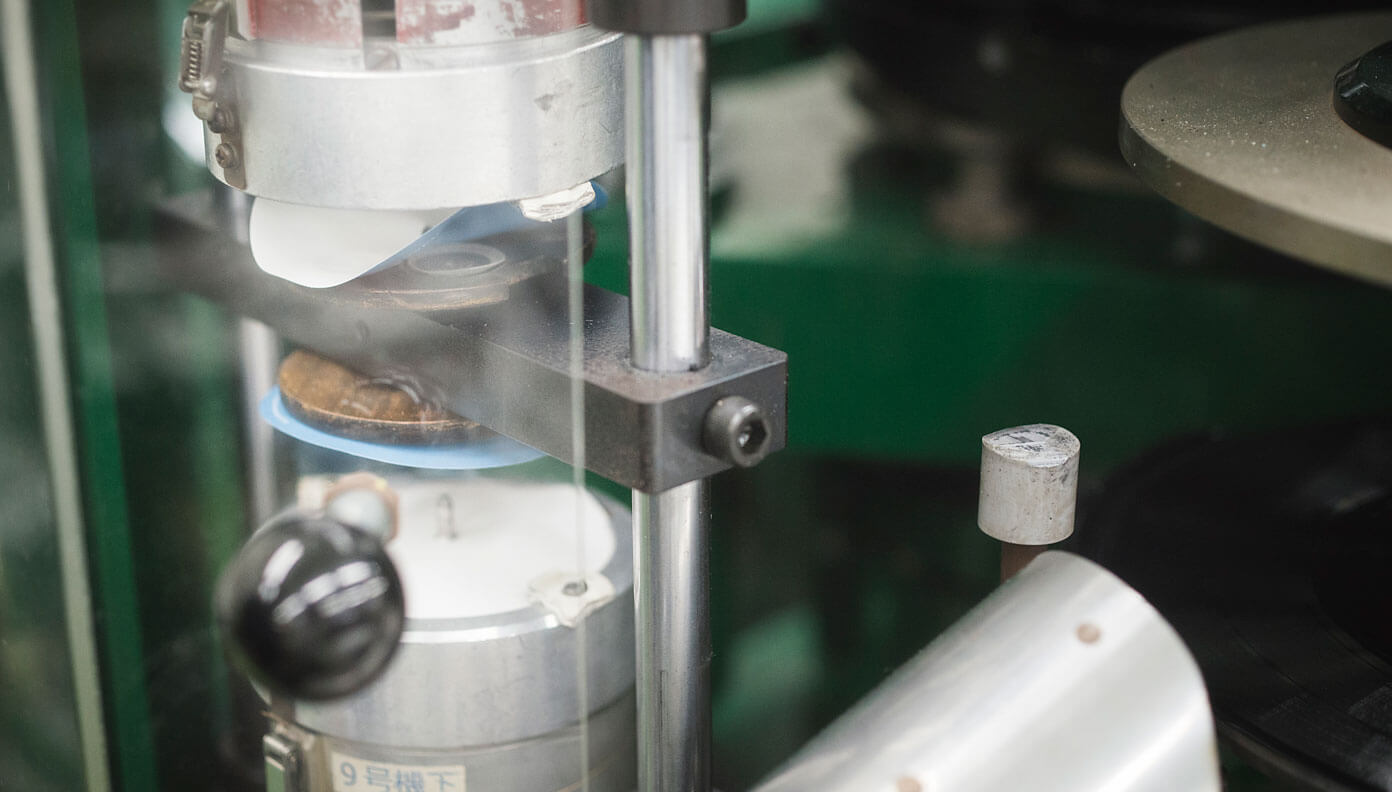

Totoku: And this is the machine where we actually cut the master. First we set an ungrooved lacquer disk onto this round plate. This plate has small holes in it, and it uses a vacuum to hold the disk tightly to it. That keeps the disk level so the grooves will be neater. Then we start cutting with this red tip. The red needle is made of artificial ruby or artificial sapphire. The machine heats and vibrates the needle as it cuts, while a small amount of helium is also pumped in to cool the disk. Sometimes we cut what’s called a direct metal master from copper, but in that case we use a diamond because it’s harder.

Record player needles are diamonds too, right?

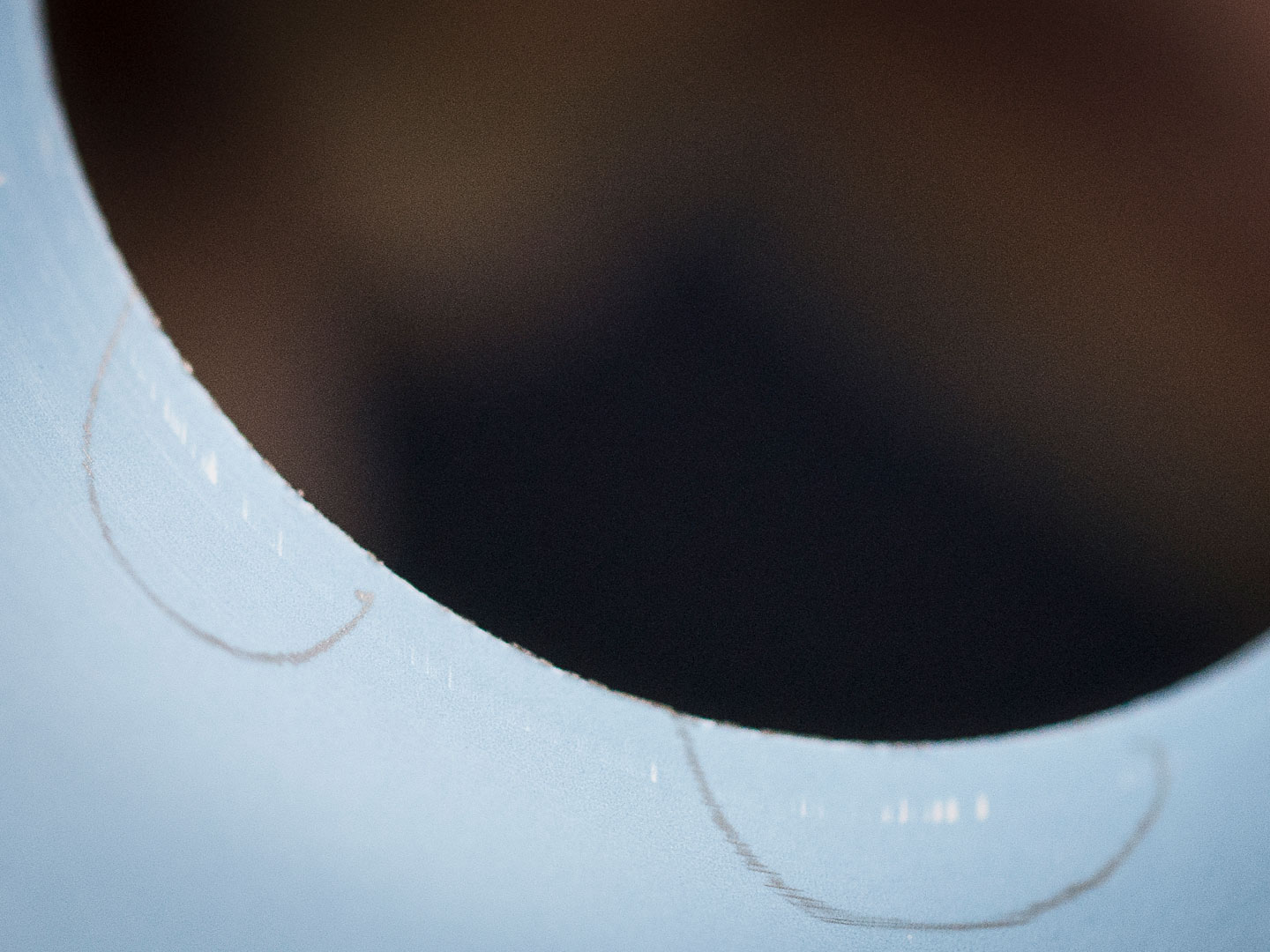

Totoku: That’s right. After we cut the lacquer disc, we use a microscope attached to a video monitor to check that there are no errors. When the grooves are stuck together, it causes the needle to jump during playback. So with this monitor we check that the grooves are separated. It magnifies the record surface 25 times, and the width of the groove is about 100 microns.

One hundred microns...I can’t picture how small that is. And isn’t this lacquer disk a little bit too big?

Totoku: It’s 14 inches.

I’ve never seen a 14-inch record. Aren’t they usually 12 inches?

Totoku: Exactly. We make the lacquer disk a little bit big so it will have extra room around the edges. The lacquer disk is 14 inches, but the records pressed from it will be 12 inches. We make the master from the lacquer disk, then we use the master to make another disk called a stamper, and then we use the stamper to mass-produce the records.

It sounds like a long process. How many people are in charge of cutting the lacquer disk?

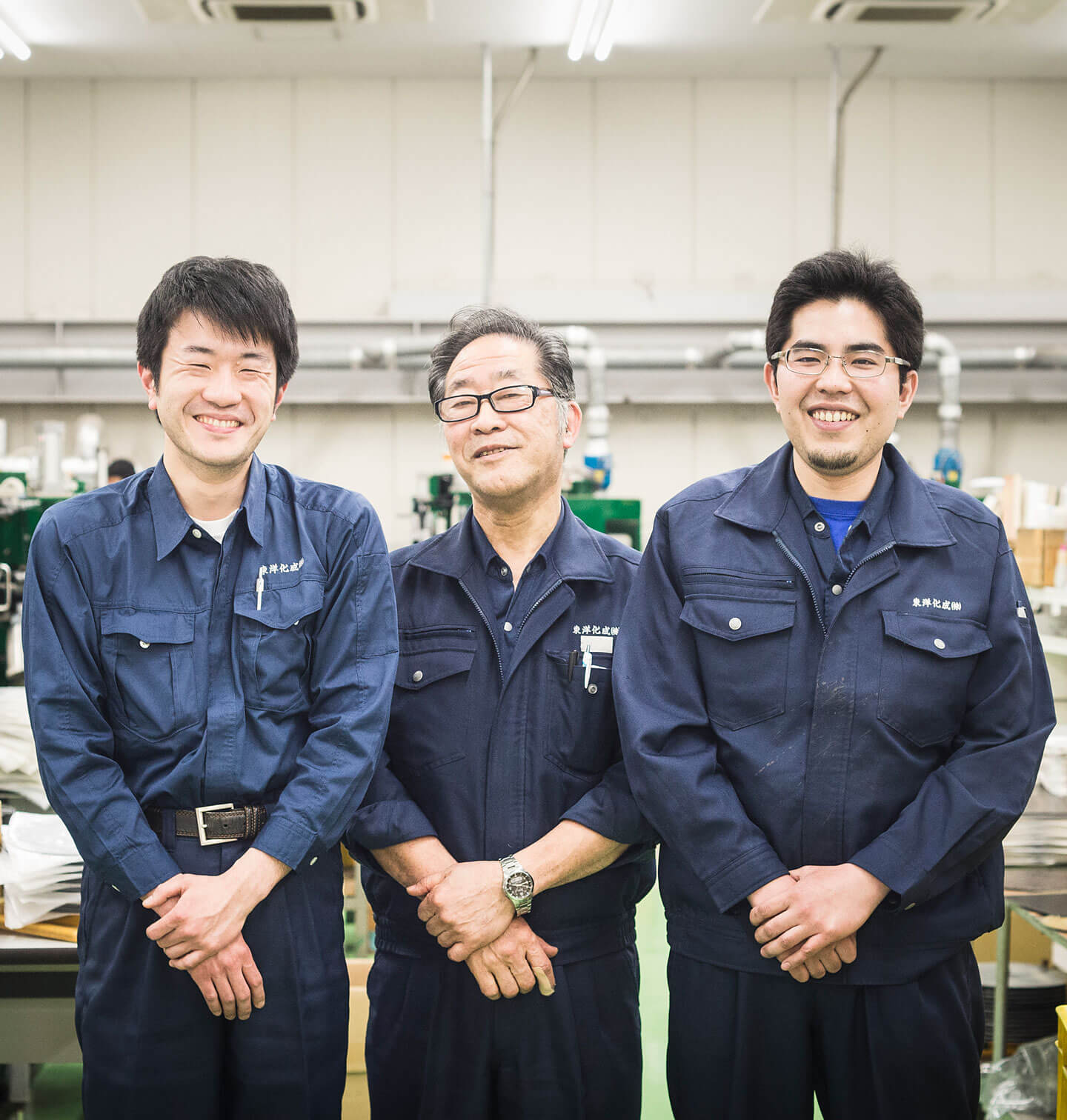

Totoku: Me and two of my superiors. So three people total.

You make them all with just three people? Do the three of you have different roles or anything?

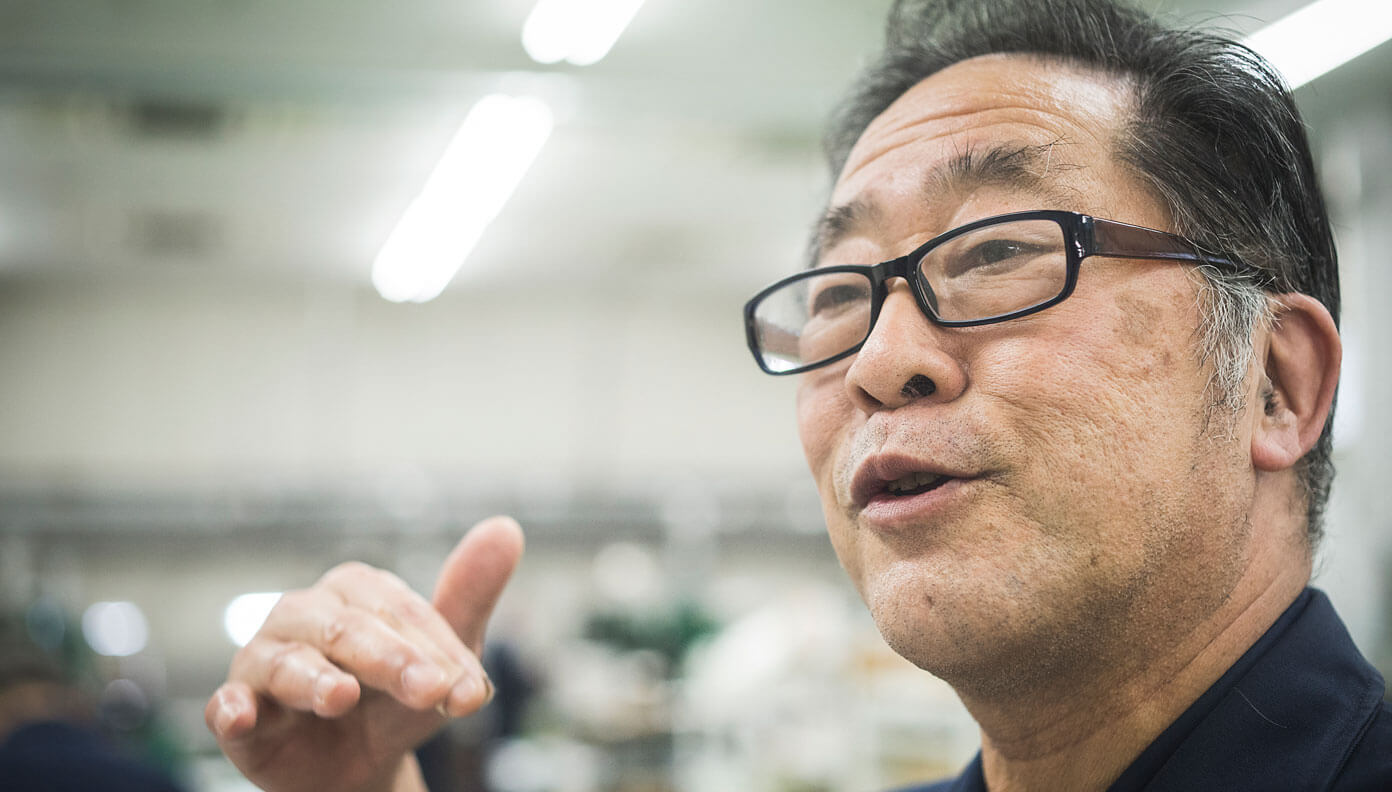

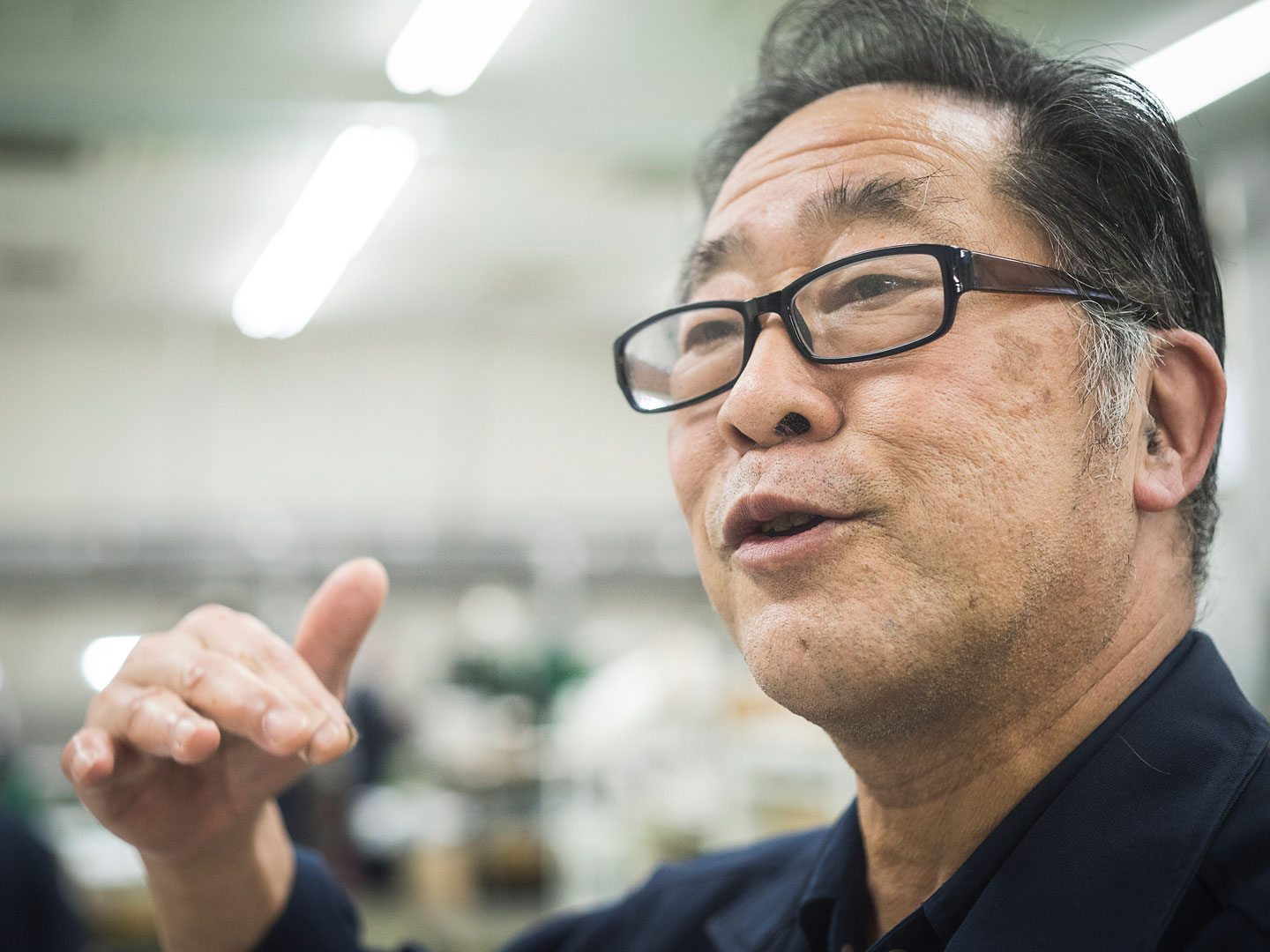

Totoku: We’re all different ages; 60’s, 40’s and 30’s. The oldest of us has handled a lot of jazz and classical so he’s good at those. I like music from that era too, but I wasn’t born then so my ears aren’t as familiar with the sound. I’d say I understand more recent music better. It isn’t a formal division of roles, but the music you listen to does affect how you cut the record. For example, even if they asked me to cut the record the same way as one of the other two, I don’t think it would turn out the same. They taught me the job, but even then it’s not the same. Whether something sounds good or bad to you has a lot to do with personal preference.

So the music you’ve listened to affects the way you make records. Have you worked here at Toyo Kasei for a long time?

Totoku: I’m 30 now, and I joined the company when I was 27, so it’s been 3 years now. Originally I was in magazine editing. Then I changed jobs and worked at Tsukiji Fish Market for a while, but I liked music and machines, so I started attending a specialty school to study musical electronic design. I was still a student there when I contacted Toyo Kasei about working here. But at the time they hadn’t been hiring for a while, so they told me they would contact me the next time they were hiring. For a year and a half after that, I would call them once every three months. But they said no every time. Of course they started to remember me. “Oh it’s you again!” (laughs) Finally one day they said they were busier than usual, and that if I was OK with a part-time job they could hire me.

You’re very persistent! Records are so much more popular around the world now than they were before. Did you already have an attachment to records when you started working here?

Totoku: I did like records then. Of course I never thought they would get this popular (laughs). Once I started working here I learned a lot more about records, but on the other hand I still feel like I have a lot to learn. For example I still don’t have the experience to handle problems when they come up. So I still need guidance from the other two to do my job.

We want to duplicate the master disk at the highest-possible quality. That’s the job of the presser.

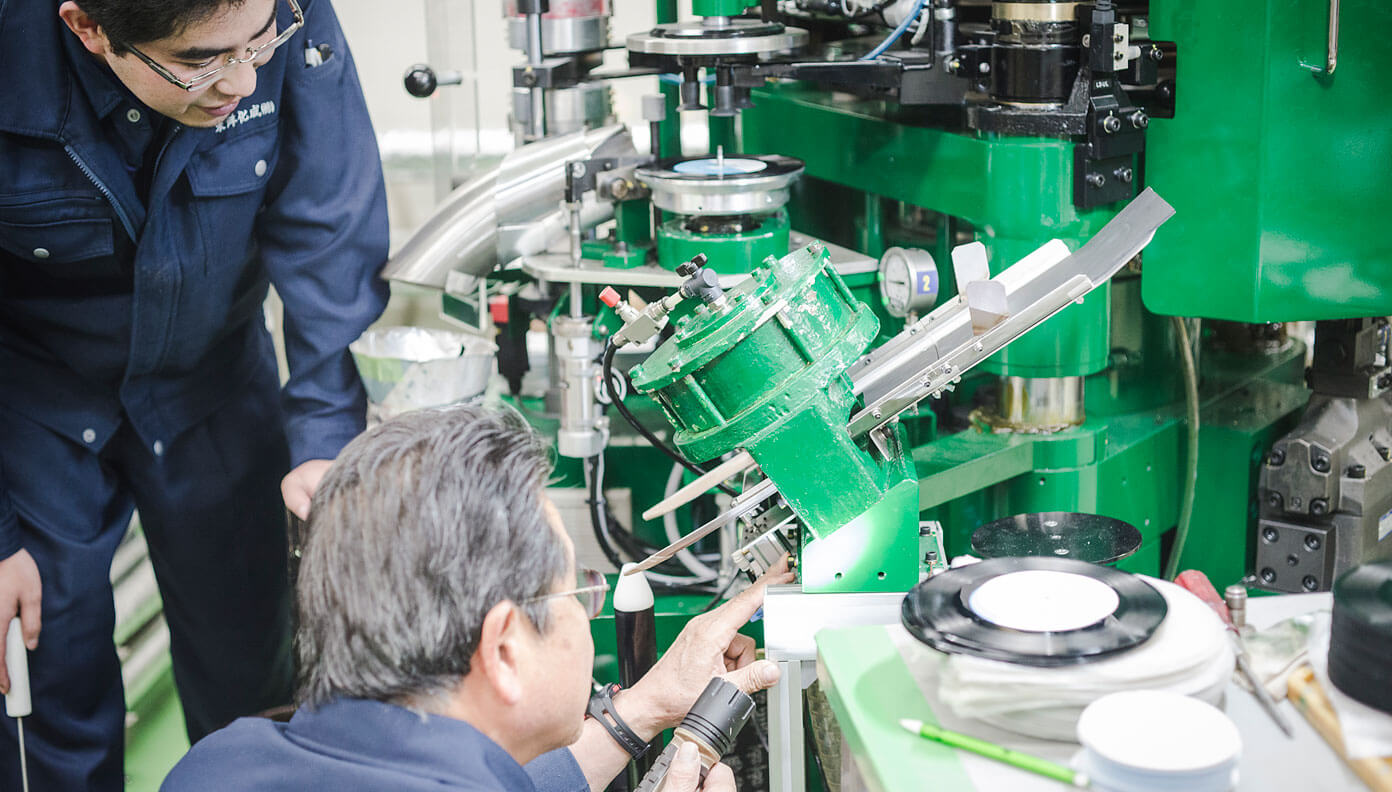

The next step after cutting is pressing. The cutting process feels more like studio work, but the pressing is more of a factory job. What does that look like?

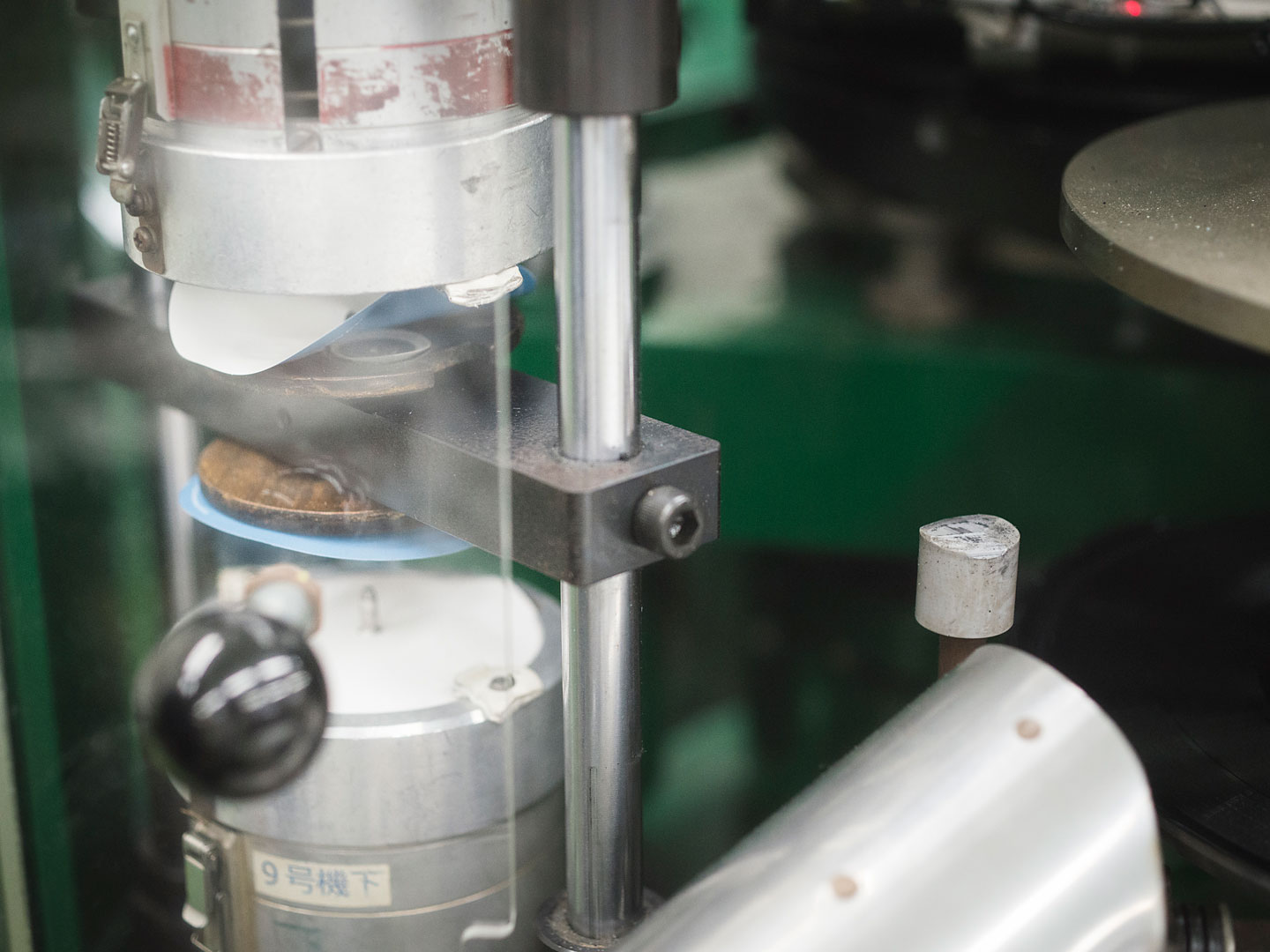

Ishimaru: Pressing is where we manufacture PVC duplicates of the master disk. First we suck the PVC material in from the warehouse with a vacuum pipe, and transfer it to the tank on this machine. We heat and stir the PVC as it melts in the tank, and then we push it out onto the machine and knead it. Here’s the PVC. We call them “pellets.”

Somehow they look like coffee beans picked from a farm.

Ishimaru: But it’s just plastic (laughs). It’s only black because there’s carbon mixed into it; it’s actually almost translucent. So you can touch it without worrying about getting it dirty. To make it clear you have to add some blue. This process is called “blooming”. Colored records are made of the same material, but with pigment added instead of carbon.

I see. I thought colored records were made from a different material.

Ishimaru: Probably because they look so totally different. But it’s the same PVC. PVC is used for a lot more than just records, like the gutters outside your house. It holds up over time. You can listen to a record even 100 or 200 years after it was made. It also doesn’t scratch easily. Records make sound by dragging a needle directly over them. So they’re made from a material that holds up to scratching. The only drawback is that PVC can warp easily.

What happens after you knead the PVC?

Ishimaru: You see labels of both sides of the record coming out ? We drop the labels and the kneaded PVC material into the center of the machine and press it so that it doesn’t slip. We press LPs with 100 tons of pressure, and 7-inches with 70 tons. We add some water during pressing. Lowering the temperature using coolant gives it a neater form. The last thing we do is cut off the excess material from the edges. We’d prefer to recycle it if we could.

Can you recycle these cuttings?

Ishimaru: When records were at their peak, they used to just bore out the labels in the middle and pulverize the rest of the material so they could re-use it. But these days there aren’t any recycling companies. PVC is reusable if you clean it properly. It only becomes unusable after seven or eight uses. Some people say that recycled vinyl even sounds better. The idea is that the more it’s kneaded, the better it sounds.

That sounds like something that would seriously interest an audiophile. Are there any special tricks for making a good-sounding record?

Ishimaru: Having done this for a very long time, I’ve found that sound quality is set by the first cutting. It’s my personal theory that you have to keep in mind the final sound of the record while you do the first cutting. First you make the lacquer disk, right? The sound quality of a lacquer disk deteriorates easily, it’s delicate. No matter how great you make the lacquer disk sound, after that you add coatings and press records and there will always be a decay in sound quality. In fact you’ll find that if the highs were really strong on the lacquer disk, they’ll mellow nicely by the end of the manufacturing process. So the ideal is to keep all that in mind and predict and reverse-engineer the final sound as you work.

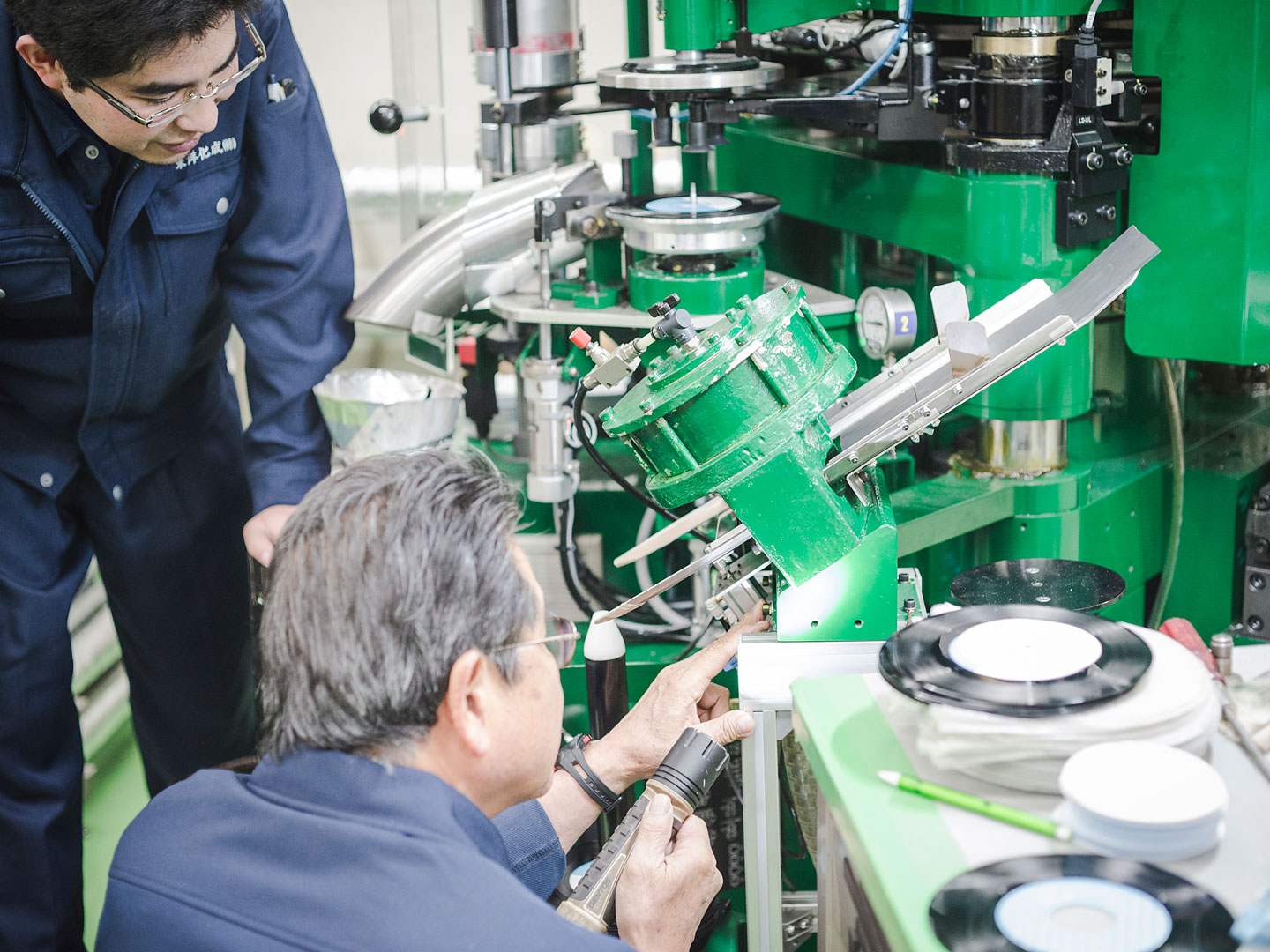

That sounds like a pointed message for the person in charge of the cutting (laughs). Is there anything you watch out for during pressing?

Ishimaru: I’m just saying I want to duplicate the master disk at the highest-possible quality. You see our young guy over there inspecting it, right?

He’s very carefully examining the surface of the disk. What is he checking for?

Wakabayashi: He’s looking at things like the condition of the ink on the label and the groove on the disk. He does a visual quality check on each disk. For example, here’s one that obviously fails the quality check.

Is this one obvious? What’s wrong with it?

Wakabayashi: This color on the label is coming off.

Now that you mention it...

Wakabayashi: The quality control at our company is extremely strict. We won’t ship things in Japan that might get a pass in other countries. From what I’ve heard it’s always been strict. I don’t know whether it’s a particular characteristic of Japanese people, but if it sounds good and it looks good, there’s certainly no room to complain.

Cutting the master, the music genre, the color of the ink, the stiffness of the paper...it all depends on the project.

What are the criteria for passing the quality check?

Wakabayashi: We make a test pressing and inspect it with our eyes and ears. I say “pressing,” but that means everything from cutting the master, to considering the music genre, to the color of the ink the customer asks for on the label or the stiffness of the paper. So how long you heat the PVC or operate the press depends on the project.

So you have to make adjustments even just based on the ink color on the label? It sounds like there are so many variables that it must be hard work to get everything right. Does experience make you better at it?

Wakabayashi: More experience definitely brings you closer to making the right choices. Now I know how to complete the entire process and figure things out by trial and error, but when it comes to really fine adjustments sometimes I still ask my superior for help. Like checking for really fine scratches, or restoration work.

Ishimaru: Even so, to be honest I think my ears aren’t as good as they used to be. Younger people tell me there’s noise on the track and I can’t hear it. My ears have gotten worse with age, but I still have my intuition. And my visual judgement has actually improved. Just by changing the angle I can see where there’s a scratch, or where the needle might jump. That’s probably thanks to experience.

How old are the two of you?

Wakabayashi: I’m 29. I started working here about three years ago.

Ishimaru: I’m 69. I’ve actually retired once (laughs). I’ve been working here for 47 years.

It’s 2018 now, so that means you started in 1971.

Ishimaru: I saw the factory in the 70s when record production was at its height. Back then each worker had to run two machines. There was a day shift and a night shift. I pressed copies of Swim, Taiyaki! (1975 children’s song and best-selling single of all time in Japan) when it came out. When record sales went down, I thought we were finished. Then they made a comeback and now they won’t let me quit (laughs).

You must be like a walking encyclopedia. Are there any other long-timers here?

Ishimaru: There are three of us you could call “long-timers.” The youngest is 67, and we’ve all retired but we can’t quit. There is absolutely no one here in their mid-forties, fifties, or mid-sixties. So we’re trying to train our successors.

I did hear that the three members of the cutting team are in their 30s, 40s, and 60s. I guess it makes sense that hiring is connected with the ebb and flow of record sales?

Wakabayashi: In a sense, I was lucky to get hired here when I did, so I want to keep learning all the skills from everyone who’s been here longer, and try to achieve even higher quality than before. Of course I want to preserve record culture, but I also want to contribute to the music culture via the records we make.

FACTORY

toyokasei

TOYOKASEI CO., LTD.

Founded in 1959, Toyo Kasei’s headquarters and sales department are located in Tokyo, and their Suehiro factory is in Yokohama. Their main business activities are record manufacturing and printing. Even after demand for analog records dropped in the 1980s due to the increasing popularity of CDs, Toyo Kasei has continued to undertake all facets of record production, from master cutting to pressing and package printing.

Suehiro Factory: 1-1-45 Suehiro-Cho Tsurumi-ku, Yokohama, Kanagawa Prefecture