INDUSTRIAL JP

idstr.jp open shareOctober 23, 2016

AT-5

goko hatsujo

interview

Continuing to take on new challenges that aren’t in the manual.

// goko hatsujo / interview

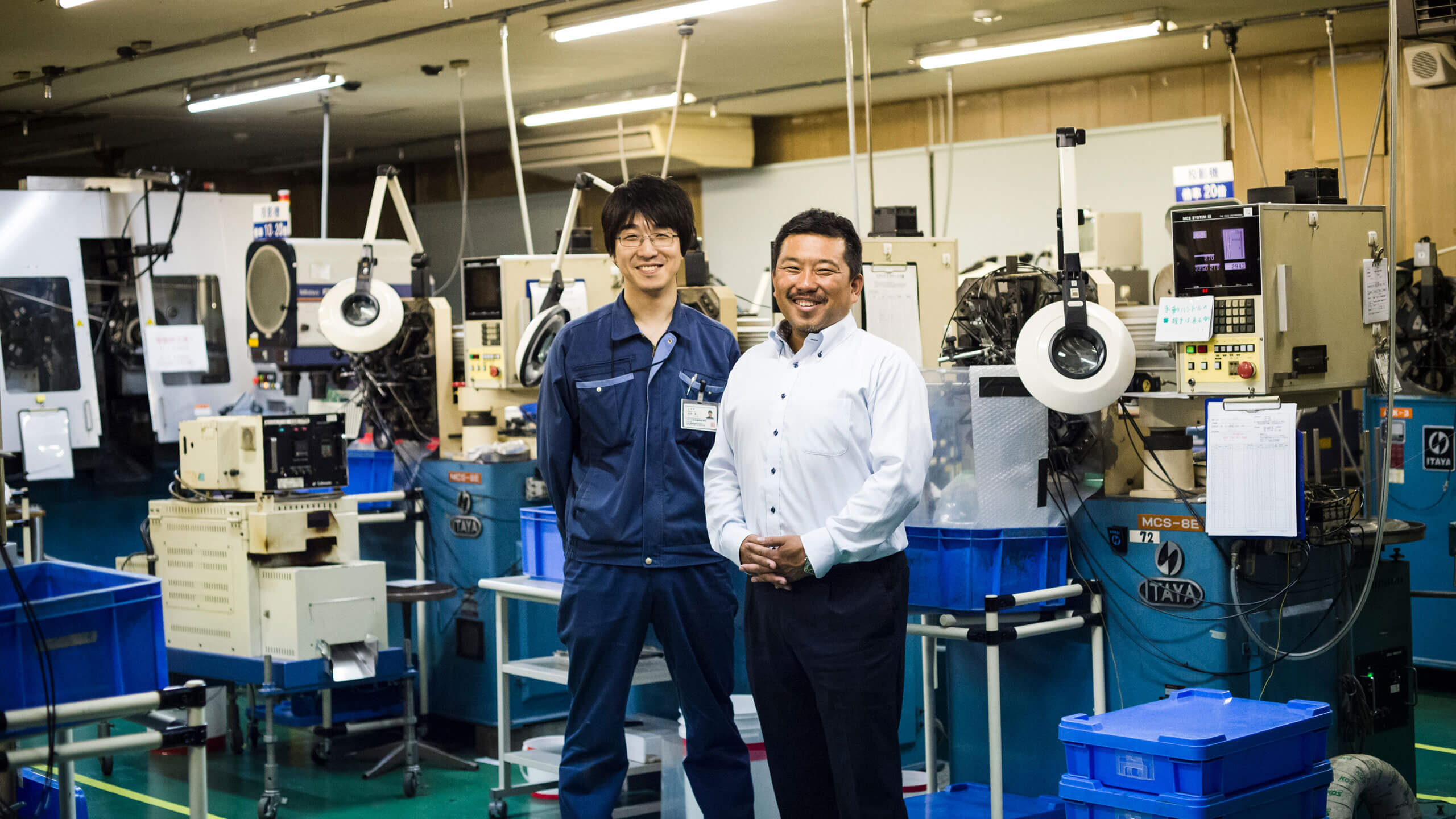

Multiple robot arms come together to make a single spring: this is one of the more memorable scenes from Sountrive’s video. The video and sound contents come from Goko Hatsujo Co., Ltd., based in Yokohama. We spoke with the President and Manufacturing Supervisor to learn more about the factory and what the robots make.

goko bane

ID-5

goko hatsujo

sountrive

It is impossible to not come across

our springs at some point in your life.

Most people know what a spring looks like, but please give us an example of where one of Goko’s springs might be used.

President Murai: It is impossible to not come across our springs at some point in your life. The most obvious example would be mechanical pencils or ballpoint pens. I think lots of people have taken one apart before. Other examples are cars, smartphones, computers, etc. However, our springs are often hidden from view. So people don’t usually come into direct contact with our springs.

Do you make any springs that are visible?

Murai: Yes, as a matter of fact in order to raise awareness of our springs, we are developing in-house original products that are centered around the spring itself.

For example, this is SpLink. I think only humans can imagine some kind of shape or idea in their head and then make it out of metal. With SpLink you can connect many small springs together to make whatever shape you have in mind.

Is this available to the public?

Murai: Yes, at “TOKYU HANDS”. “LOFT” was selling it about 2-3 years ago although they no longer do. This was our first original product. Since it was our first one, we incorporated pop culture things like cats so it would sell better, and made pen stands so they would be displayed in stationery sections.

When I came here to talk springs, I didn’t expect the subject to change so quickly to something other than springs. Though I realize they are still springs.

Murai: We also make a card stand. We call the brand “Factionary.” Usually you see plastic card holders. It’s a little bit difficult to make a metal card holder that is angled and easily seen on a shelf. Our spring stand is stylish and adjustable. People love it.

One way we came up with for our business to survive in Japan is to stand out.

Was it your idea to make these products, Mr. Murai?

Murai: SpLink came to me very simply. I realized, “you can make anything with this!” Even I was impressed. I used some prototype springs to make a fish shape, and everyone around me thought it was great. It was the first time I’d ever felt that way at work. Usually I just make things according to plans that my clients give me, and I’d never used metal to make something so soft.

Since it was your first original product, did you slave over the prototype?

Murai: Actually the first prototype was a size smaller. We thought we’d use the smallest size we were capable of making, thinking you could make more details with it. But when springs are small they’re too stiff, and it hurts your fingers to play with them. So we settled on this size that is easier to play with.

We want to make a larger size that you could make things like chairs, but we’d need more material, and there are a limited number of machines we can use. And there was no way we’d use the machines to make our prototype when they were needed to fill a client order.

In the face of that, why did you decide to make this original product?

Murai: We get most of our orders from home electronics makers, but home electronics aren’t doing so well in Japan now. To survive as a spring maker you have to have a stock of technologies you can use, and you also have to figure out how to get the attention of customers who would rather take their business overseas if it’s cheaper. One way we came up with for our business to survive in this country is to stand out. First we want people to know about us. Also springs are usually sold for less than one yen per piece. To make them more valuable, we have to have technology and methods that no one else has. So we’d like to create original goods to raise the value of our springs. It’s rare that a brand can be created using just the technology small factories already have. We hope people will take notice.

The last steps of our processing are always manual, and performed by sight. We’re very particular about how we do things.

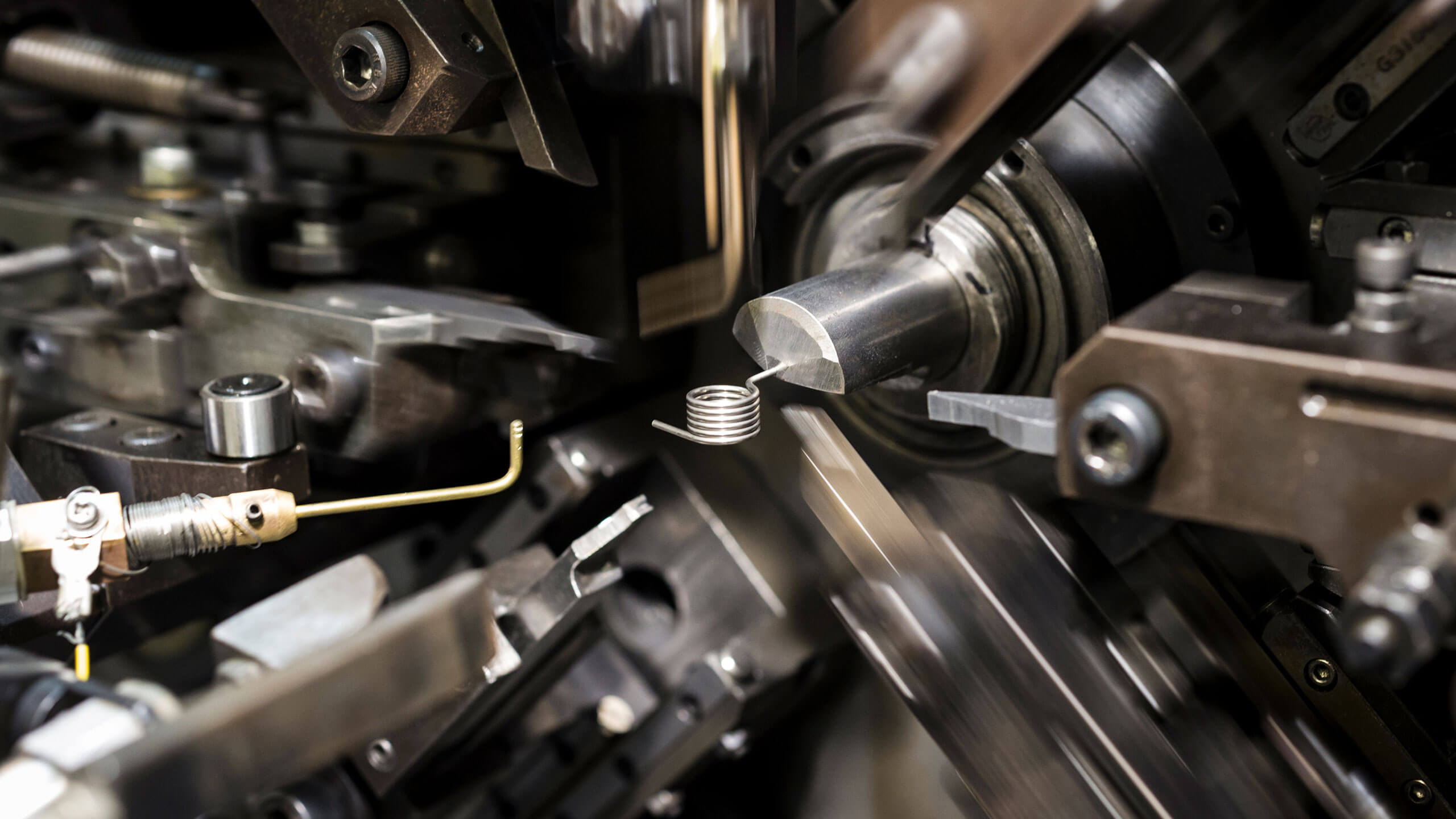

So you make the product using this machine, right? There are so many different kinds of arms. Do you use all of them?

Yamamoto: We generally use all of them. We change their configuration according to the product being made. We also make more complicated shapes where the parts move to the right or the left. We change the thickness of the material depending on the product, so of course the parts we use also depend on the thickness of the material. We also test whether changing the parts will damage the product. And the tips of these parts are adjusted by hand.

You adjust the tip of this wire by hand? When I look closely I see that each one is unique, and they have a handmade quality. These are all adjusted by sight?

Yamamoto: It’s the only way you can do it. We look through a microscope to dig the grooves and match up the ends. We’re very particular about how these handmade parts are made.

Are the configuration and movement of the arms set ahead of time, or do you do it on site?

The client sends us a design of the springs they need. But the design doesn’t tell you how to make the item. If they just want “the usual,” we just make it like we always do, but for other things we have to come up with a way to make it. Each spring maker would do it differently, I imagine. Everyone’s got their own way, since each company has its own particular knowledge of how to shape the spring and how much pressure to apply. Every single spring is unique.

I see. So there are standard recipes, and also original products.

Yamamoto: That’s right. The most basic thing is to make springs that will work. Some springs will break if you just make them according to the client’s design. In those cases we might even apply our company’s own know-how to make something completely different. We’re stronger as a company when we can make something that would break if anyone else made it.

So the people who make the designs are not all spring experts?

Yamamoto: We’re the experts, so naturally we know more. Of course some things have to be done in cooperation with the client. We send them the prototype and they put it in their product to test for durability, and sometimes it fails. They provide feedback, and we continue with our development and design.

With social media and cloud services, factories with technology to spare are getting matched up with people who want to start new ventures.

If you don’t know what product a spring is for and where it goes, it seems like it would be tricky to design it. Do your clients ever explain it to you?

Yamamoto: They generally just give us the design. Rarely do they tell us what the spring will be for.

Murai: And lately more and more people with design skill are moving overseas.

So there is a movement overseas. I hear that you are developing a factory overseas as well.

Murai: We have to keep up with the times. When a small factory like ours is developing an operation overseas, we might seem bigger than we are. But really it’s just that we can’t survive with just a Japanese operation, so we’ve been forced to expand.

Where do you find the value in continuing to make springs in Japan under such difficult circumstances?

Murai: There have been developments in social media and cloud services, and a lot of new businesses are teaming up with manufacturers. Factories with technology to spare are connecting with new designers and creators on Facebook and other places. More and more people in Japan are attempting to make new things. But those people don’t know anything about springs, so they ask us to make them from scratch. We get requests on our website that say “I need a spring that fits here,” and we work with them to design one.

I see. I’ve heard from a friend of mine that even if they can design a prototype, the next steps of building and mass producing the product are difficult.

Murai: About three or four years ago I started visiting a place where entrepreneurs gather. I want to tell people about our springs and make connections. One product that won a design award used springs that we made.

And we succeed precisely because we don’t have a manual to work from. Every new set of design specs is a new start.

As you continue to make springs in Japan, is there any production value that you can only get because the product is made in Japan using Japanese technical ability? Like the spirit of our craftsmanship?

Murai: I don’t know whether you’d call it technical ability or the spirit of craftsmanship, but it’s our policy that when we receive a new order, we never say we can’t do it. We often take requests that other companies turned down. We start with choosing the material, and by the time we’ve tried this or that, we end up doing things that other companies couldn’t do. Things that other companies can’t do seem very ordinary to us. We don’t notice it much, but maybe our technical ability and the spirit of craftsmanship come from our cumulative experience and attention to detail.

So to you it’s so ordinary that you’re not conscious of your skill.

Yamamoto: When people say “you’re doing something so difficult,” that’s the first time I realize that it’s difficult. When meetings during the prototype stage, of course we sometimes think something is difficult, but many times we’ve managed to pull it off anyway.

Murai: Actually we’ve done something that no one else in the world has been able to do. We received an order to make a medical device part that was only 0.020mm thick.

Yamamoto: It took three or four days just to run the material through the machine (laughs)。

That’s a tall order (laughs). Was it difficult to make?

Yamamoto: I guess it was difficult, but work is what I enjoy most. I love to prototype it and perfect it, then stabilize it and get it made. There are so many possible kinds of springs you can make if you start to think about it. And the material is actually not that smooth. You have to deal with all those factors to make a good product. That spring-making facilities are so developed is due to so much cumulative development. And that’s why it would be hard to put it into a manual.

When you can’t put it in a manual, the technician’s know-how must be difficult to convey.

Murai: That’s right. But even though it’s hard you have to do it. You have to keep track of it somehow because you can’t just depend on your memory. We’re trying to use video to somehow leave a record.

On the other hand, it may be because there is no manual that we succeed. Every new set of product specs is an opportunity to try something new. Sometimes we make a point of trying things a different way.

Yamamoto: But sometimes you get stuck trying and failing to make the same spring for two days (laughs).

FACTORY

goko hatsujo

GOKO HATSUJO CO., LTD.

Goko is a small wire spring manufacturer founded in 1971. They have two factories in Japan, one in Yokohama, and one in Yamanashi, as well as factories in Thailand, Vietnam, and Indonesia. They specialize in designing, developing, and manufacturing ultra-precision springs. Their springs are used in everything from medical devices to cars and motorcycles. They can produce a single prototype, or fill monthly orders of tens of millions of units.

25-16 Gokanmecho, Yokohama Seya-ku, Kanagawa 2460008 Japan