INDUSTRIAL JP

idstr.jp open shareOctober 23, 2016

AT-3

shin ei idstr.

interview

We’re very particular about making a variety of products in small quantities. That’s why we believe in the power of people.

// shin ei idstr. / interview

Shin Ei Industry in Hanamigawa-ku, Chiba city. As we approach the factory, we begin to hear the loud sound of the press machine processing metal. This sound, and this footage, will become the basis of a video with music by DJ Gonno. We’re about to interview Mr. Nakamura who is the second president of the company, which was established 35 years ago, to ask about his commitment to his work and the company’s products.

shin-ei press

ID-3

shin ei idstr.

dj gonno

We mainly make our products by “Single Operation Mold Processing”. Most factories won’t do that since it takes so much work, but we make a point of it.

The press machine is working now. What are you making?

First we have home and exterior goods, like sheds. Then we have wire brackets, which hold electrical wires in place. When we make electrical wires or electrical devices, we have to make them in accordance with electrical construction laws. Japan has some unique electrical construction laws, maybe because there are so many earthquakes. In China there are some places where they just stick the wires to a wall with some tape and call it a day(laughs). Sometimes they don’t even insulate them or ground them.

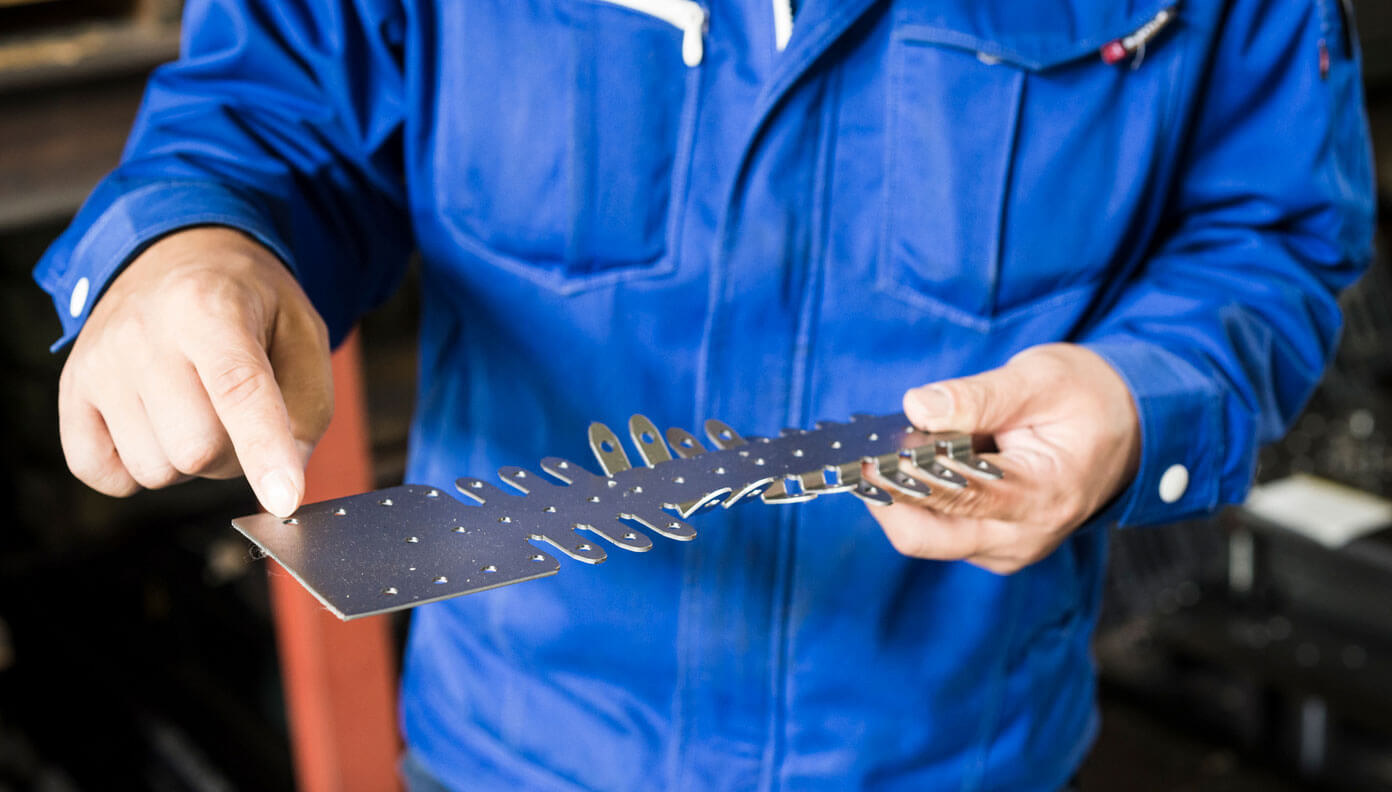

Most of the things you’ve been focusing on in the video are called “progressive mold processing,” where we lay out long material and process them one after the other. But that kind of work is usually done with mass production, so a lot of it goes overseas now. That’s why progressive mold processing manufacturing only make up about 30% of our operations.

The main 70% is from “single operation mold processing,” which is when you place the material in the press and press the buttons one at a time. It requires more work, and someone has to stay with the machine at all times, so most factories don’t like to work that way. But we make a point of doing it. It’s become our specialty, and even though the situation in Japan is hard, we aren’t affected much by ups and downs in the market.

Which parts do you design by hand?

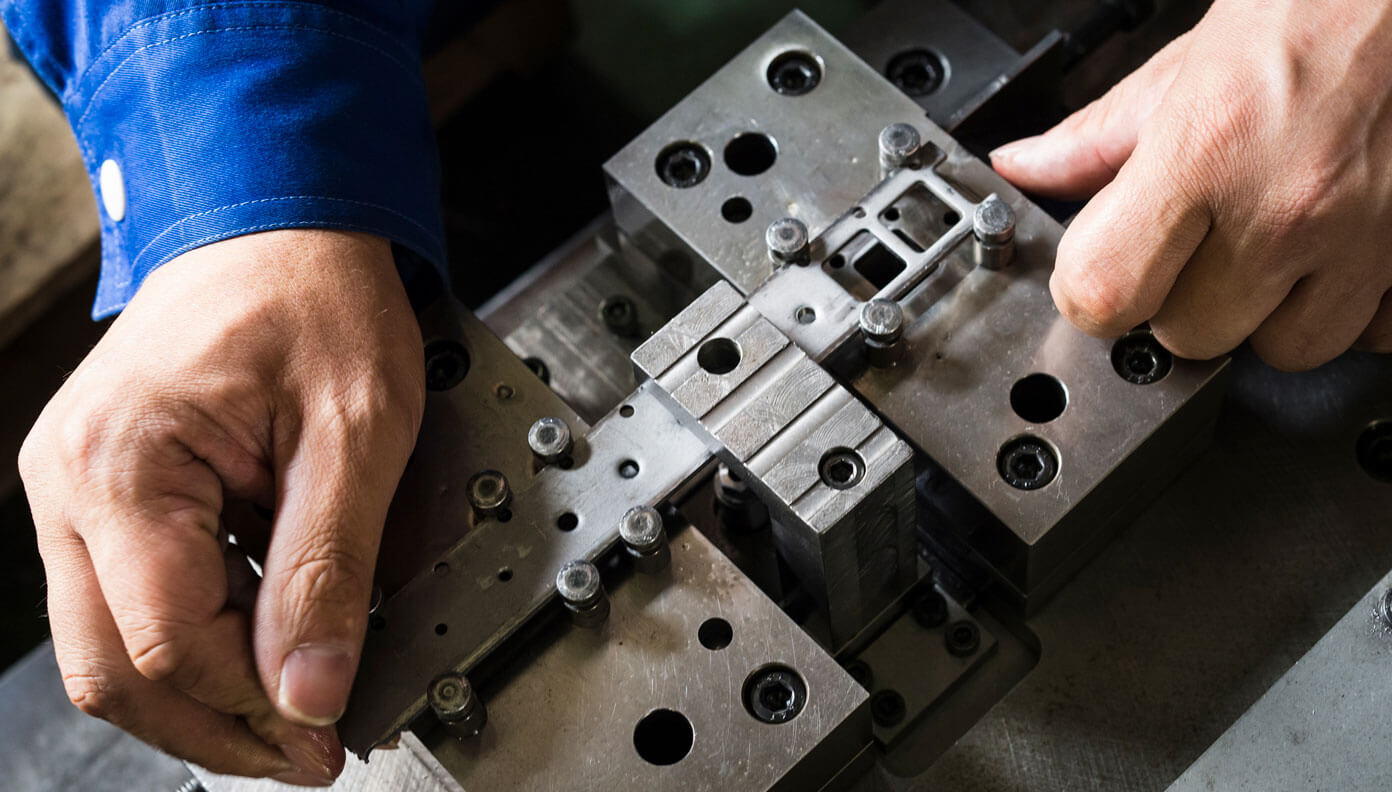

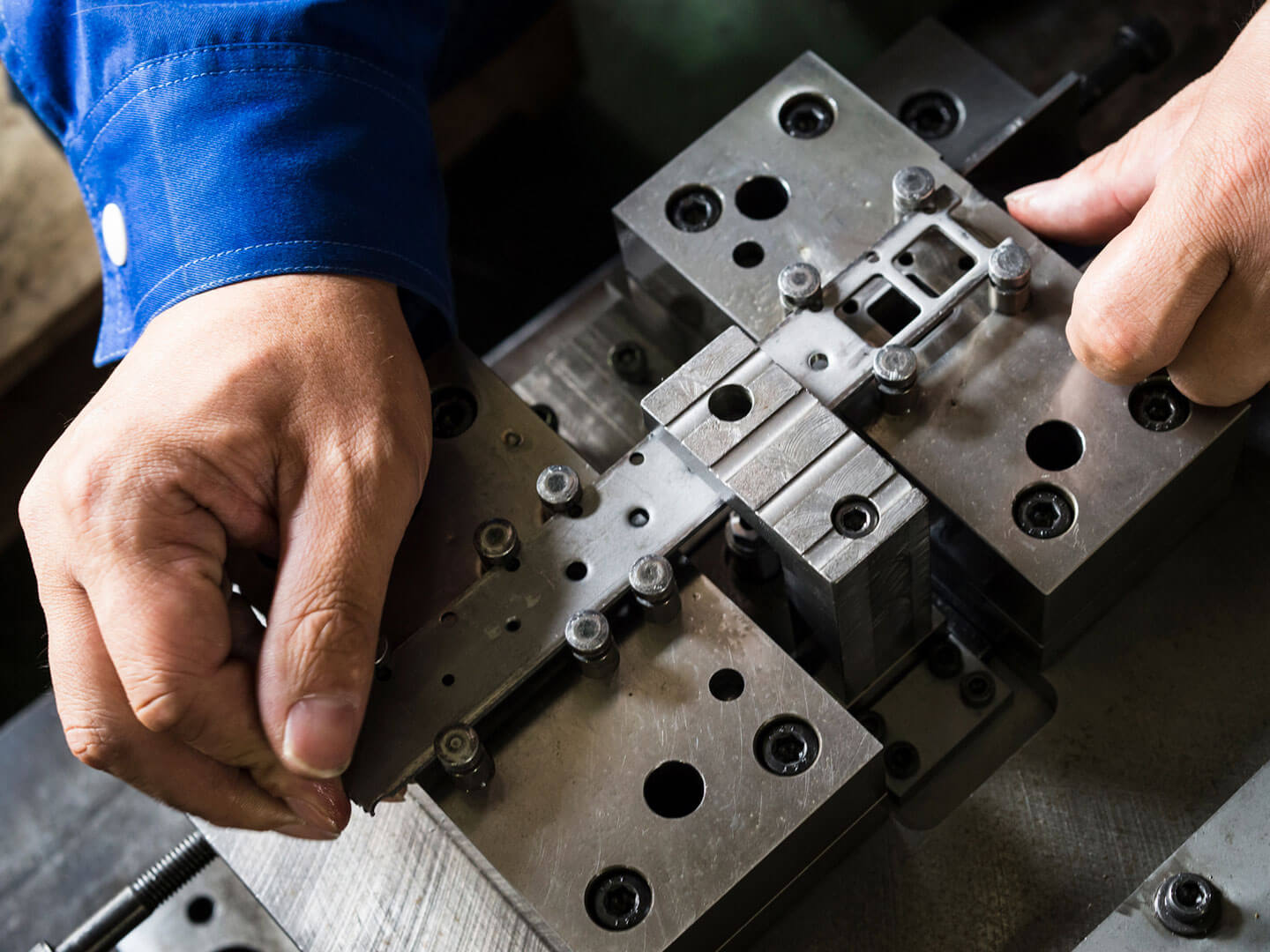

The molds. The things that a manufacturing site is most careful about are that they don’t make anything defective, or that they don’t miss delivery deadlines, and the heart of that is the molds. If you continue to work using damaged molds, you’ll continue to make defective products. In the case of single operation mold processing someone is always with the machine, they can see any irregularities and halt operation, butit’s a much bigger problem for continuous processing.

Still, if you’re performing maintenance after defects appear, you’re already too late. There’s something called “shot maintenance,” where we decide ahead of time the maximum number of shots to be made. Once the press has made the specified number of shots, we send it to maintenance even if there are no irregularities. That’s why it’s rare for a machine to break down in the middle of production. When it breaks down during production, it also takes a psychological toll, like “Whoa, really? I have to finish this by tomorrow, what am I supposed to do?” But with all the people we have working here, only two of them are in charge of molds. We’re stretched to the limit.

So each time you press something, you count one “shot.” How long does it take to make a mold?

We take about a month to make one mold. But it is only durable to press for a few days.

I see. So everything depends on making the mold. It looks like there are various sizes of mold. How are they different?

Put simply, the longer a mold is horizontally, the more stages it has. “Stage” refers to a stage in processing. Each mold has multiple stages. And with each shot, the material advances one more stage. That’s how progressive operation works. But in single operation, we use a different mold for each stage.

What is the maximum number of stages?

I guess about twenty stages. Some patterns require ten successive operations, but processing continuously can lead to irregularities, so you have to take a break sometimes. So there’s one stage called “idle,” where you don’t do anything.

“Idle,” like an idling car?

Right. On the other hand, sometimes we perform the same process twice, just to be sure. Sometimes you think the material has bent the first time, but it hasn’t bent all the way. So it hasn’t been bent enough. When that happens, everything you’ve made is ruined. Metal has a thing called “springback,” where it tries to return to it’s original shape after you bend it. For example, if you want to bend the material 90 degrees, sometimes you have to bend it more than 90 degrees. So after we bend it more than 90 degrees, we ensure proper measurements by adding another stage where we bend it back to exactly 90 degrees.

Have you ever played “Dragon Quest”?

An iron sword or a steel sword, you know which one is stronger, right? (laughs)

It must be hard work to plan out which process should happen when, or when you should insert a rest. It seems like there are infinite possible combinations.

The molds we use at our company are designed by our own tech people. Sometimes we get them made by third party mold makers, and in that case they’re designed by that maker. All the client asks for is a particular shape; we decide how to get it made.

It must be hard enough to decide the processing combinations, but isn’t the processing itself sometimes difficult too?

I wouldn’t say it’s “difficult,” but engraving is certainly taxing. Press engraving can crush metal. So it takes a toll on the material, on the mold, and on the press. We prefer not to do it too often. (laughs)

Engraving is that taxing, is it? (laughs)

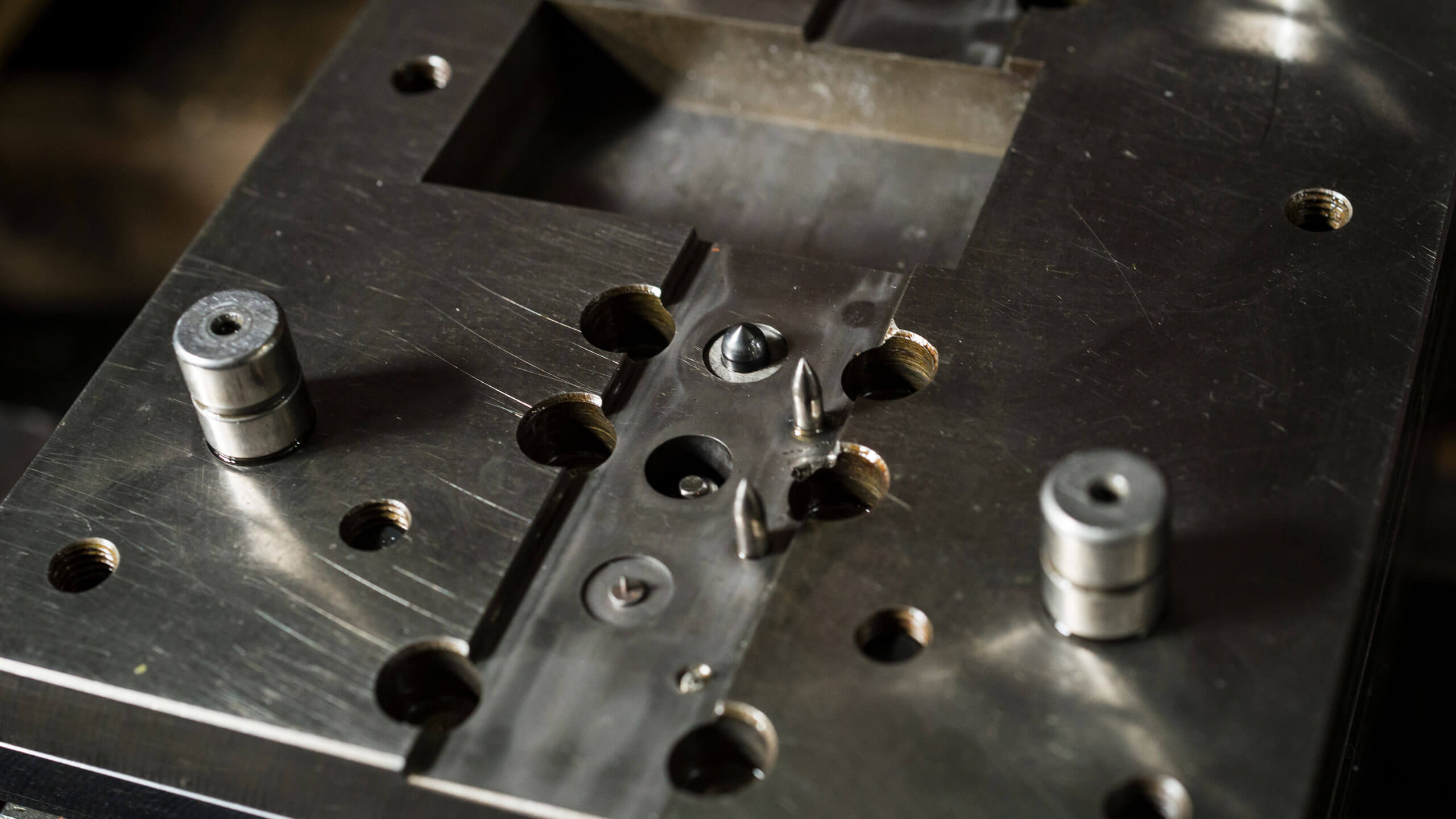

A mold is like a blade, in that it gets dull the longer you use it. When it dulls it negatively affects the product. So they require maintenance. Like when you sharpen a blade so it can cut again. Or you might temper it. Have you ever played “Dragon Quest”? There are iron swords and steel swords, right? Iron cannot be heat treated, but steel can. If you’ve played Dragon Quest, then you know which is harder or stronger.

I’ve played “Dragon Quest”, so I understand. (laughs) Where do you temper it?

Just at the edge. When you scratch the iron part with metal it leaves a mark, or you can file it down. But a tempered edge is really hard, so you can’t scratch it.

And so that’s why it’s fine no matter how many times you press.

Yes, but then you might think you should just make everything out of steel, right? For example, depending on where you use a mold, you might want to avoid making it from steel. Iron has endurance and pliability, so it’s strong against impact. Steel is very hard, but it will split if something happens to it. For example, plates made to absorb impact are made of iron.

So you’re saying that harder is not necessarily better. You have to know the material and its qualities.

We might also change the type of steel. We use normal steel for blades to press soft material, but for pressing stainless and titanium we make the mold from super-hard alloy. So it won’t be damaged by the hardness of the material.

Mold design is a job for someone inquisitive who work in silence. Someone who can work by trial and error in their own little world.

I see. So they think of which stage to use, which process, and where to take breaks, and also which parts to use in processing. They have got a lot to think about.

They sure do. Designing molds...it’s a job for someone who is inquisitive and works in silence, rather than someone with communication skills. It’s not exactly a “geek,” but it’s got to be someone who can work by trial and error with their own little world.

Which must mean there’s a craftsman for this part. On the other hand, is there a job for someone with good communications skills? (laughs)

The actual processing. Because everyone has to work together.

So it’s cooperative play. When you say “craftsman,” one might imagine a person who uses their artisanal skill in actual manufacturing, but that’s not quite right, is it? It’s the period between testing and execution where the technician really shines.

Our company has an advantage because we can prototype the mold, and test it and adjust it in-house. If that weren’t the case, you’d have to look at the results of a test-pressing and then send it out multiple times to get adjusted. And when it gets worn down and broken from use, it’s a boon that we can handle the maintenance ourselves. Because we’re always fighting to make a deadline.

When I work hard, they say “it’s because I have to be CEO one day”. When I’m lazy, they call me “the stupid son.”

Has the factory always been here?

Yes, for the most part. It was founded by my father’s family.

You’re a second-generation CEO, right? Does being the second CEO create any unique issues for you?

For better or worse, when you’re the founder, you can always make it work, even if you have an attitude of “it’s my company and my job and anyone who doesn’t like it can quit.” But the son can’t get away with that, you know? You didn’t make the company, and while your parents are still around you’re just in middle management. So even when you work your hardest, people just say “he’s only working for himself, so he can become CEO one day.”

I see (laughs). So you slack off instead?

If I seem lazy, they call me “the stupid son.” (laughs)

It’s a more difficult position than I thought (laughs).

Well, a lot of that went away once I became CEO. When I was in middle management, the worst times were when I had to run things even though my employees didn’t believe in me. Now that I’m CEO everything is my responsibility, so I can do things how I like and it’s much less stressful.

As CEO, is there a particular area you’d like to focus your energy?

I’d like to make products with more added value, and take on a greater variety of work. A product with high added value is one that has been more processed but remains the same size. To put it another way, bending both ends of a large piece of material is low added value. For example, at a 300-square meter factory, simple arithmetic will tell you that it’s more efficient to make small 10-process products, than to make large 10-process products. It’s difficult to manufacture in an ordinance-designated city like Chiba, since the land is so expensive.

I see. So where would be a better place?

Somewhere outside the city in the country would be better. Land and labor are both inexpensive. When it comes to cost, I can’t beat a rural factory. My minimum rent keeps changing, and so do worker salaries. It’s getting tough to stay in Chiba. But then we are blessed when it comes to delivery. We’re right in the middle of the factories in Kashiwa, Urayasu, Funabashi and Narita. So we stay here because of our advantage in distribution.

Pressing plants deal with larger products, so the amount of space you have and processing of products become more important to run a company.

That’s right. That’s why I want to increase the types of products we handle. Like electronic parts, for example.

So you need a press to make electronic parts too?

There’s a press machine for small products like electronic parts. But to make small, thin things, you need very fine molds. Even with the same error range of 10%, it requires a totally different level of processing technology if you’re going to make something 1mm thick or something 5mm thick. Because you have to bend it just a little bit, with just a little bit of pressure.

I understand that making small things has its own particular difficulties. Are some things also more difficult because they’re so big?

For big things you usually just need enthusiasm and brute strength (laughs).

The original design papers don’t include parts that have been worn down by use,

so ultimately it’s up to human strength.

I see. Craftsmanship is quickly moving in the direction of smaller, more detailed items.

But actually you can work that out to the extent that it depends on the precision of the machine. Another thing we’d like to work on is variety. For example, this was made by cutting a rod in a machine and adding screw shapes at both ends. Next we’re going to bend it in a press and make the product. What makes it different from bending pipe is whether you can bend something that’s solid all the way through. So you can only make this at a press factory.

Of course you can’t do this processing with only a press. How did you end up able to make new products like this?

I just ran around looking for someone who knew how, and got them to teach me. We make custom-sized products, and our customers can specify height and pitch down to the millimeter. We deliver custom products with short turnaround. And we can do that because our technicians are older. Small order manufacturing can’t be mechanized, so ultimately it depends on manpower. Our company depends a lot on manpower.

Does “manpower” mean you use tons of employees?

That can be true too, but in this case it means “ability that only humans have.” For example, If you’re going to make a mold from scratch, you can just make it according to the data file, and use CAD and 3D printers, so human hands aren’t required. But for maintenance, you have to look at the actual thing and adjust it accordingly. Parts worn down from use are not included in the design plans. So that’s why human power is ultimately needed.

I want my employees to take pride in their work. So it makes me happy that you’ve made this video that will make them feel that their work is cool.

So you would like to continue to use human power to make a larger variety of things in small quantities, here in Japan. Do you have any other wishes or ambitions for the future?

In the future...you might say this is small thinking, but I want my employees to feel lucky that they worked at my company. Small batch jobs are hard to standardize or automate. It sounds nice to say it requires manpower, but it sounds less nice to say it requires that my employees work really hard. So it depends on creating a good working environment. In order for Japan to keep going, we have to take care of the workers, and that means improving work environments.

What do you have in mind?

I want to compile a database of our processing requirements. I’d put a data entry station at each machine so workers won’t have to depend on their memory. Factories that make the same thing over and over just standardize it so anyone can do it. But sometimes we don’t make the same thing again for three months, and the workers forget. Up to know we’ve kept track on paper, but there is so much paper now that it’s hard to organize. It will be faster and easier to have a database.

So you want to make a smoother work environment.

Yes. And I want to make their jobs even just a little bit easier. Also, I watched that footage and I felt so happy. I want my employees to take pride in their work. If you can’t put something of yourself into your work, it’s hard to feel proud of it. Especially since for the first three to five years of working you’re just doing as you’re told.

As you say, when you’re only doing what you’re told, it really is just “work.”

I do ask them things like “Why do you think that is? Try figuring it out yourself.” But it’s harder to get them to have a sense of ownership of their work. So I’m really happy that you’ve used video and music to make this thing that will make my employees feel like their work is cool, and take pride in it. I’m grateful.

It would also be rewarding for us if they feel that way. By the way, do you usually listen to music?

Yes, I used to play drums in a band.

So you’ve probably felt that the sights and sounds of the factory are like a music video.

Yes, like industrial music.

Earlier there was an employee at that press over there wearing earplugs and making huge banging sounds. We heard that sound and wondered how we could use it. We just thought it was so cool.

I know what you mean, but that noise is tough to listen to every day (laughs).

FACTORY

shin ei idstr.

Shin Ei Industry CO., LTD.

Shin Ei Industry was founded in 1979 in Chiba-City, which became a major distribution center with the opening of the Ken-O Expressway. Centring around metal stamp manufacturing, Shin Ei makes metal dies, and provides packaging services as a one-stop manufacturer and shipper. They use surface treatment material, stainless steel, and aluminum between 0.6mm and 3.2mm, to create small batches of many products. They can design metal dies according to “lifelong lots”, devising optimum manufacturing techniques.

1304 Amadocho, Chiba Hanamigawa-ku, Chiba 2620043 Japan